John Lydon:

Vox magazine, March 1992

Transcribed by Karsten Roekens

© 1992 Vox / CHRISSY ILEY

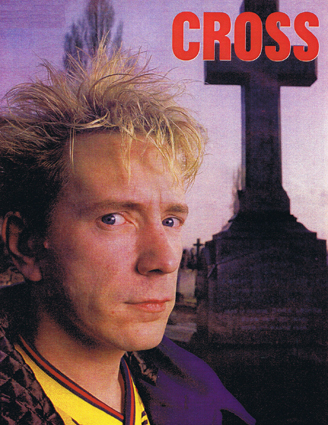

CROSS EXAMINATION

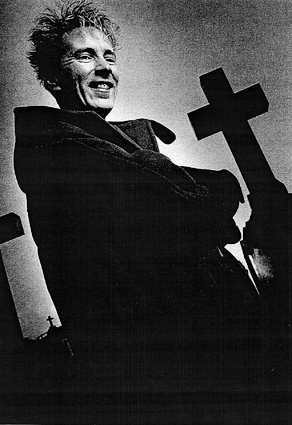

John Lydon feels the time has come to tell the real story of the Sex Pistols. He also explains to CHRISSY ILEY how The Stare came about, how he feels ugly and shy, and how David Bowie got the inspiration for Tin Machine. Grave images by BARRY MARSDEN.

John Lydon feels the time has come to tell the real story of the Sex Pistols. He also explains to CHRISSY ILEY how The Stare came about, how he feels ugly and shy, and how David Bowie got the inspiration for Tin Machine. Grave images by BARRY MARSDEN.

He still sits with a slovenly recklessness. His hair is still splashed blond, his attire a succession of colours violently ill at ease with one another – a green and purple plaid woolly lumberjack shirt over the widely reviled Arsenal away-strip all topped with a Cadbury's coloured violet duffle coat. Here's Johnny doing his best to cause a clash.

The voice is still sing-songy, spoken with the kind of pang that makes it sound like a snarl, even when it is not. Lydon's mouth is set permanently between a smile and a snarl.

And the questions that every journalist since 1981 has asked still arise. Is he the Antichrist? Is he still a rebel? Has he mellowed with age and the cosseting of Nora? Is he still nasty? I last met Lydon five years ago and it was hideous. He dismissed me.

"Dense as a forest! You're boring me, get out!"

And I did. He doesn't remember this.

"I'm afraid, you left no lingering impressions. Was I bored?"

The voice comes out tetchy and Fagin-esque.

The new record, 'That What Is Not', is a step away from the ordinary melodic rock of 'Happy?' and the too tingly '9'. It closes with a chunk of 'God Save The Queen's "No future, no future!" A return to nihilism?

"No, no. 'No future' is not nihilistic, it is quite obviously honest. There isn't much of a future, not for any of us. Optimism is where you leave yourself open to be let down. I expect the worst, I can never be disappointed. There's nothing morbid about 'No future'."

Lydon is gleefully negative.

"Why not enjoy your misery? Even good things can be dismal, why not?"

Lydon comes complete with props. The words "Why not?" are one of them, he uses them seventeen times in the first ten minutes. It means he doesn't want to answer the question, or that it's either too boring – or too interesting.

The other prop is more curious. It's his brother Bob, perched on the sofa. Forgettable but for the rather gashing scar that divides his face. There's no explanation why he is there. Possibly to unnerve interviewers and calm Lydon. In the same way that Lydon used to like to surround himself with unfortunates, with heroin addicts (although he never touched the stuff) – it made him feel more secure to have such wretchedness around him. So the more aggressive he is, the more vulnerable the journalist. And if they get nasty, he can always get nastier. It might be a good idea to break that pattern.

He says he doesn't care whether 'Cruel' is a hit single, but:

"I'm not in this as a charity. I'm not greedy, I'm not pandering to an audience, and for that I should be respected."

There's always that hankering – respect, it's right up there in the Lydon Top Ten of demands. I realise, if you don't run away, he won't heckle. If you show him respect, he'll tell you good stories and he'll listen to yours.

What do you think of Tin Machine?

"Don't understand it."

Did you know you were responsible for it?

"How so?"

He draws near, eyes aglow. I tell him Bowie's son, Joe, is a huge fan and that his favourite album of all time, 'Metal Box', inspired the very being, Tin Machine.

"I'm stunned! I met Joe, he came to one of our gigs and brought his daddy along. Daddy bribed the bouncers to get backstage."

Apparently Joe wanted daddy to be like John.

"There are references to the Pistols in Tin Machine. Mmm. Mmm. We all stood there staring at each other sheepishly, extremely foolish. They came two minutes before I was going on stage, which annoyed me. I was extremely nervous at that point and I thought it insensitive. I'm not into son and heir stuff, that's for insecure arseholes. A lot of people use their kids as ego extensions. It justifies their dismal marriage and boring life – 'I'm doing it all for them!'" he mocks, with the voice high, the eyes beady. "Right now, if we wanted a kid we'd go and buy one!"

Nora, now a grandmother, is long past childbearing anyway. She is the mother of Arianna – formerly Ari Up of The Slits. She's older than Johnny by some 14 years, though she doesn't look older than him. She looks a bosomy, biddable blonde. She's Austrian and moneyed, healthy and by all accounts incredibly attentive. He is fiercely protective of Nora.

"I'll kill any journalist that slags her off! She is a closed door. If anyone dared interfere I would do them serious damage!"

They've been married twelve years. He doesn't want to say how they met or anything about her. But from ancient cuttings in a teen mag, where Johnny Rotten was writing his diary as early as 1977, there was a lot of eating curries, watching 'Crossroads' and staying the nights over at Nora's. Nora is probably the only woman alive who knew how to handle him. Or is it mother him? I myself found that I was uncharacteristically slipping into the maternal, as I watched him spike his ears with a biro.

You'll ruin your ears doing that! You're pushing the wax in!

"Well, I've been doing it all my life. How else am I going to get those annoying, crusty bits out? Oooh, soaking wet! Do you think I've punctured something?"

But this is a mere display, for I have already discovered John Lydon, the sensitive man.

"And is it so strange that I can be sensitive and caring?" he whines tragically. "If I get pricked by a pin, it hurts. If someone drives a nail into my heart ..."

And now we're getting into Shylock. Lydon conjures up the man he most loathes. His every twitch is resonant of him. His sing-songy twang. He hates him, yet he reminds me so much of him. I dare not even speak his name. But when Lydon is thinking of the stake through the heart and he speaks of a whole succession of managers as a breed, it seems inevitable. He is thinking of the generic Malcolm McLaren.

And now we're getting into Shylock. Lydon conjures up the man he most loathes. His every twitch is resonant of him. His sing-songy twang. He hates him, yet he reminds me so much of him. I dare not even speak his name. But when Lydon is thinking of the stake through the heart and he speaks of a whole succession of managers as a breed, it seems inevitable. He is thinking of the generic Malcolm McLaren.

"I don't cry. Never. Only with rage. Never in a movie or rubbish like that. Liars enrage me, deceit, financial skullduggery. Although none of this is recent, in fact, I haven't had a stake through the heart often enough. I deserve more attention! Obviously I'm only half the man I used to be, a shadow of my former self!"

He cackles.

"Although being in a band we are at each others' throats continually. That's part of the excitement, that's what makes the energy. Winding people up is definitely a good thing. They know how to get at me! But I'm not going to tell you, because then the general public will know and be onto me!"

There's more cackling and bantering and puns rumbling, until the mention of Jon Savage's book 'England's Dreaming'.

"Hopeless! Not interested! Next!"

Affronted silence.

"What he's doing there is fantasising, inventing theories and over-elaborating. What I've got to say is the truth, the reality. Action and truth."

What he had to say to Jon Savage was nothing at all. He refused to appear in documentary about the book, and because of it, neither did the documentary.

So when he says: "My book will be the truth, the whole truth, nothing but. It will start at my birth and end with the demise of the Pistols," when he says: "Without me the Pistols wouln't be anywhere, and neither would the whole so-called punk movement!", he has a point.

"It was all centred on me. It might sound egotistical, but it's the fucking truth. And I don't believe in being humble for the sheer hell of it. I'm a third of the way in, it's hard to remember, there are whole years missing! I have to ring up everybody I know. Of course I can remember the slap – 'the doctor didn't like me, grabbed my ankles, held me like a turkey. Mommy, why did you let him hit me? I knew you didn't love me.' When I was born I was 40 years old, a fully developed miserable git. Now I'm approaching childhood. It's all theatrical, I realised years ago that all human emotions are merely acts. We use them to distance ourselves. What we truly feel we don't understand."

With a smile/snarl he adds: "And there's shock value in being nicer! Now I can be nice to people to shock them, it's very irritating to a lot of people. They come planning war, and a nice guy sits down."

He has to say that, like he has to make an excuse because we're getting on okay. Does he really feel he's changed?

"I've got bigger and fatter and taller, funny that. You're not supposed to grow after 18, but I have. Maybe I'm a retarded sort, late developer. But it's on my passport – I've grown six inches since I was 21. I used to be a tiny, ratty thing, now I'm 5 ft 11. But I've not calmed down. I like to rant and rave like a Rottweiler let loose."

Predictable now, he puts the pen to the ears and plucks.

"I'm a better person now. God obviously looked out for me and decided to give me a helping hand. Let's face it, he made me as ugly as sin. I had to improve somewhere."

Do you really think you're ugly?

"Yes. Very much so."

After a considered assessment where I find all the bits to be in the right place, if not in the right proportion, I find him generally appealing. I don't tell him that because he won't believe me. I just say, I don't think you're ugly.

"Ears are too big, got buck teeth, got nasty eyes. Nose wrong, bit chinless, hunchback, pigeon chest. Got a big breast, not breasts. Fat arse, nobbly, vile feet, fingers need a facelift."

This is the point in the interview where Bob gets up to ask Virgin Records to order him a taxi. And this is the point where John becomes entirely approachable, disarmingly so. It's as if all he needed to be told in the first place was, look, you're not ugly.

Did you develop your persona out of ugliness?

"No, out of shyness. I was extremely shy when I was young. Still am really. Can't bear even rehearsing, drives me mad. Don't mind jumping on stage in front of 20,000, but if it's one to one in a rehearsal room, I crumble. I'm permanently red-faced, blushing like a beetroot. And then there's the vomiting! I always puke before I go on, because I'm so tense. I'm doing a tour for this album, so I shall be hugheying in your neighbourhood soon. I'd never forgive myself for doing that during the show. How awful, they'd say I was on heroin! I combat it by not eating, not anything, the whole day. I'd be violently ill. I don't drink on tour because that puts you into a false sense of security one night, and the next night you've got a vile hangover. Experience has taught me how to be less nervous. That is a permanent part of me. I have only overcome my shyness to an extent, I can't stand parties or crowded situations where you have to talk to many people at the same time. That confuses and irritates me."

I tell him I think he is coming dangerously close to ruining his image.

"Everything written about me contradicts. I am all things to all people. The trouble with this flippant pop business is, you're not supposed to move on to something different. You're not supposed to move on to something different. You're supposed to stay in the slot allocated to you."

The demon can be reconjured easily if you ask for the story of The Stare. You know, that stare. The zombie-ate-my-soul stare. The eyes that perpetrated the myth of the Sex Pistols. It could come out on a tiny stage or in a stadium.

"I was very quiet at school, didn't cause distractions until very late. At 14 they threw me out and I had to go to a special school for problem people. I used to question everything. But I found a favourite way of staring, not blinking, and that used to drive the teachers crazy. Unnerved them, worked a treat. I got kicked out for staring! It sounds bizarre, but it worked very effectively. I could do it for a good twenty minutes. You don't focus on anything, you keep at it. Drives them up the wall! They can't work out what you're thinking, and it looks like you are thinking very aggressive thoughts, that is their presumption. I was probably thinking, when can I leave this boring class?"

Can you do it now?

He obliges. And even to order The Stare still shocks and conjures those punk days. There's so much anger concentrated in it, it looks evil. It's just a stare, but I want to say stop, please! I'm actually shuffling, and I can hear my breath coming in deep gasps.

The eyes are so small they don't look human. But it's the story of a life in a face. It's as grizzly as a dismembered body, too awful not to look at.

Did you ever doubt that without this man there would be no punk movement?

![]()

© BARRY MARSDEN