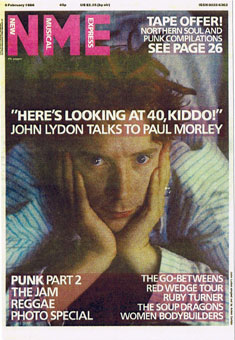

John

Lydon:

NME, February 8th, 1986

Transcribed (and additional info) by Karsten Roekens

© 1986 NME

THIS IS WHAT YOU GET

Smug, rich and articulate, ''nobody's failure'', JOHN LYDON flits between video shoots and keeps PAUL MORLEY entertained with tales of ordinary madness. Still sessions by ANTON CORBIJN.

This is the beginning of an interview with the John Lydon who has

drunk seven cans of Red Stripe lager, after breakfasting on oysters.

This is the beginning of an interview with the John Lydon who has

drunk seven cans of Red Stripe lager, after breakfasting on oysters.

Lydon: ''I know you want me to say loads of witty things here. But I can't be fucking bothered. I'm not interested in making myself out to be God's gift to the universe with glorious germs of wit.''

Morley: ''My God, you're boring.''

Lydon: ''Yes.''

Morley: ''And so fat.''

Lydon: ''Yes.''

Morley: ''And very ugly.''

Lydon: ''Yes... so why are you here? You people waste endless hours of my life and parade such silly prejudices about what someone like me does. You get it wrong time and time again and expect me to patiently put up with your small-time ignorance. I'm still expected to live in a squat in Hackney and be everybody's little failure. Well, I'm not interested in that. What a boring lifestyle! You come along and you're nice as pie to my face, and then you go off and write something as bitter as sin. British pop writers just love failures and scruffiness, they never look further afield than their own stranded indulgences. Well, I won't have it. I put up with it every now and then for a bit of amusement, but... really!''

Morley: ''Is this the punk speaking?''

Lydon: ''See what I mean? What can I say? It's all so dreary. And people still view me because of the crap that's been written about me over the years. That I'm difficult and snobby and violent and terrifying and awful and always pulling attitudes. Well, it's all rubbish. I just don't need it.''

Anger, truth, crossed destinies, scorched flesh, antique medicine bottles, nostalgia and patterned underpants. Down a small alleyway behind the Lost Property Office at King's Cross Station: cynical slapstick, snide camels, sex, cabbage and danger. It's a video shoot. Large white sheets dangle from washing lines, candy coloured confetti is blown through the air by a wind machine, a singer bites off a foreskin in sudden rage.

One more vital video permutation of fluff and nonsense: the favourite

form of farce for today's lustful senseless seekers. We are diverted

by two fornicating dogs and a prostitute named Helen. A Victorian chimney

sweep ducks Van Dyke in favour of early Gielgud as he stands motionless

in front of a white sheet. E. E. Cummings counts all the confetti.

The cameraman works small wonders to take in the glory of the cracking

clouds behind the singer's head, while the singer lets the good fairy

drink from the cup of his navel. What exceptional tomfoolery. The small

director in the padded jacket plans his grave fun and poeticised claptrap,

the singer with the pert little nose effortlessly contrives a frantic

menace. For no reason at all really, the singer comes alive for a second

or two to mime

a line or two of his relaxed, curious new song, in front of the saucy

sheets, amidst the twinkling confetti, under the spreading chestnut

tree.

''I could be right / I could be wrong''

John Lydon the singer lets fake pain drain from his body, steps away from a white sheet that had coiled around his legs, flicks the confetti from his hair. He walks away from the hundreds and hundreds of frogs towards earthly realities. I smile in sympathy at his unlikely predicament.

Lydon: ''Caught me unawares, haven't you?''

Morley: ''A likely story. I just never thought I'd see you trapped inside a video.''

Lydon: ''Well, you have. I thought I'd give it a

go. A now that I've found out that it's all

as bad as I thought... things will change. It's an appalling piece

of nonsense, but you do your best to be nice through it all, don't

you? Thank God this is just a small part of my life.''

Morley: ''What is?''

Lydon: ''Pop music. I just don't need it.''

This is the beginning of an interview with John Lydon, the sickly, trusting, awfully vain English eccentric drinking neat gin ever so sweetly.

Lydon: ''Oh no, English eccentric! That's terrible... I'm not Viv Stanshall. I'm not one of the Bonzos. What do you want me to say here? 'I'm not normal. I know I'm mad...' There, I've said it.''

Morley: ''In what way are you mad?''

Lydon: ''I'm not dull. Not nine to five.''

Morley: ''This is not much of a major achievement.''

Lydon: ''No. But it will do. There's different ways of being nine to five. Lots of pop musicians run from nine to five. I think Sting at the moment is fast doing that. I wonder why. If I see a schedule coming close, I exit. Because I only work in short bursts – and I feel this is totally wise – I am prepared only up to a point to go along with the many misfortunes attached to making a record these days. I'm afraid I don't agree with doing things that I don't enjoy. I can afford to do that, so why not? I'd be a fool to do it any other way. Why make my life a misery if I can make it one of utter joy?''

Morley: ''The lazy English eccentric.''

Lydon: ''Look,

I never tell anyone what I'm up to, and so the little pop writers

can't judge me with sarky comments. I give out to those people who

apparently judge people like me these days – God bless them – nothing

to work on. I don't fit. If this makes me lazy, so

be it. As for being English, I will admit to that. I couldn't be anything

else. I have an Irish family, but I'm so bloody English it's not true.

I've got blue blood in my veins! But I don't need to live in England

to be that. That's what I don't like about the English, you're not

supposed to move out without it being some terrible betrayal. If you

leave you're selling out! Selling out what? I call it expanding. Being

open to new horizons. Progress. I find it essential. Like, I'm bored

stiff with people complaining about the French and never going there,

or just going to the obvious places. They have no concept of what the

French are

at all! I do, and they are awful.''

Morley: ''Perhaps what I mean by English eccentric is: fussy social judgements, fastidious sensibilities, honest self-regard, someone who in their work and presentation sets down life's actual juxtapositions, contradictions and convolutions, for a kind of comic relief.''

Lydon: ''Well well, who'd have thought! You're not

alone in the view that a lot of what I do is funny, but I'm not sure

I agree with you. I don't live my life as a joke on everybody...

as for what it is that I do, I'll leave the conclusion about that to

my public... who I do everything for. That reminds me, whatever

happened to Larry Grayson?''

Morley: ''He died a death.''

Lydon: ''Thank God for that.''

Morley: ''Just like you.''

Lydon: ''Thank God for that! Look, I'm not going to rise to any bait. I won't assume the role of injured party in any clash of wills. I just don't need it.''

A small ordinary car forces its way through intimidating early evening traffic, creeping from King's Cross Station towards a film studio in Fulham. The singer, a backseat passenger, punished by a weakened lager and a bursting bladder, grumbles like Albert Steptoe suffering from acedia, the deathlike condition of not caring. He's being moved from singing along with sheets, sweeps and steady creeps to a new setting: Mount Sinai, apparently. Confetti is giving way to burning bushes and storms of blood. The singer left the sheets behind, feeling it wasn't too bad a way to brighten up a drab day. In the car boredom drops on his head with seemingly pre-arranged abruptness.

Lydon: ''I'm a worm! I'm a God!''

Steeped in Beckettian gloom and futility that a relieved bladder cannot change, the singer quietly growls at the uniform tedium of the world. Everyone else in the car is boring, he ticks them off one by one.

Lydon: ''You're boring, you're boring, you're boring. You're all boring.''

He assumes the role of a slothful hero and curses a hard life and a confined world.

Lydon: ''Another set of light on red. And another. Another. As punctual as a hangman.''

This is the beginning of an interview with John Lydon, the man whose eyes adore him, whose laughter is cruel, the rakish villain, proud and miserable.

Lydon: ''The world is slowly crumbling to a halt, and in ten years time I think we're going to see a very bad phase. I can see it coming. I can see how it can be stopped to...''

Morley: ''Oh yes?''

Lydon: ''People are fools... and that's the way it is. Always have been, always will be.''

Morley: ''You're not going to wipe the generalizations from your eyes.''

Lydon: ''Well, history is one of my favourite subjects, and you can see catastrophe repeating itself time and time again...''

Morley: ''You're a history student now?''

Lydon: ''I always have been... hehehehehehe...''

Morley: ''From 1976 and all that to history.''

Lydon: ''Well, when the Pistols formed I knew what

would happen. I knew it would all end in misery. It had to! Where else

could it go? It speeded it all up, knowing where it would end up. There's

not very much you can do about such glorious inevitabilities, so enjoy

it

for the moment. That goes for everything. Ultimately you're not at

the steering wheel. You're a passenger.''

Morley: ''Do you have any standard liberal concerns for the rest of the world?''

Lydon: ''Sounds a little grim to me. I care for this human... oh, and Nora, my wife... and one or two others dotted around the world. But not the species. Why should I take on all that work? Seems suspicious to me if anyone does. Oh, you look hungry, take all my money.''

Morley: ''You hate the current illuminated guilt?''

Lydon: ''It's pathetic. And it's all used by huge political machinery. This dismal exploitation of people's guilt and anxiety has been going on for centuries... And Geldof... well, his heart's in the right place. Between the ribs. So... he's being manipulated. What more needs to be said. It's all much more subtle and intricate than it appears to be.''

Morley: ''You're basing your disinterested comments on your great historical perspectives?''

Lydon: ''Well, my view is based on fact rather than a fear of Bob Geldof.''

Morley: ''The fact of what?''

Lydon: ''The fact this thing will continue. Bangladesh comes to mind. Look at what happened there. Lots of goodwill and then what... compassion is small time next to the weight of history.''

Morley: ''You say this is cushioned by money.''

Lydon: ''Yes. So? I'm sitting in the lap of luxury

while it's available. While stocks last.

Nice work if you can get it. I've not got enough money. There's no

end to my greed! Guilt?

I just don't need it.''

This is the beginning of an interview with John Lydon, who jigged and fagged his way from poor Islington to light Los Angeles, via this, that and the other. From plain poverty through the groggy desires of punk to an exquisitely inconsiderate, quite sophisticated happiness. Still No Future and a fear of nothingness, but now... corrupted only by refinements.

Lydon: ''Yes! Isn't it wonderful?''

Morley: ''So where have you been these past few years?''

Lydon: ''I've been in my own world. Everything around me is of my own making. I am my own man, responsible to no one.''

Morley: ''This is luxury.''

Lydon: ''Of course, but I went out and organized it for myself. I know what I want. I know what suits me. It's relatively simple. Lou Reed did it, his own little world. It just happens. Then you look at what you've got and think 'That's really nice, I really like me.' It's all hindsight. None of us are that brilliant.''

Morley: ''How did you see your future at 16?''

Lydon: ''Well,

it couldn't get any worse. I could only go up. There was poverty,

misery, working class slouchiness. I wasn't going to have any of

that. Surely here I'm setting the proper example. Get out of it!

Go forward, young man. Don't wallow in the council flat misery. There's

no joy in that. I could never enjoy that dullness, I knew there had

to be ways out. I never liked being a kid. But I knew it could only

get better. It's always been like that – I've

thought 'I can wait.' Patience. I never understood the jealousy for

rich people that there was on those estates. Like, 'Oh look at those

rich bastards in Belgravia.'

I always thought 'Well, that would be nice.' That's something to look

forward to, not down on. If you look down on it, that's inverted snobbery.

That's not healthy. That just eats away like a worm inside. But now

I have to earn more money on my own terms. It's not anything I've planned.

You can't really make a decision about your future at 16. The schools

pretend you can, but that's rubbish. You'll end up making a terrible

mess. Whatever I like at a particular point will suit me fine. If I

don't like it then I'll move on... away from it. And that's what i

do. I find lumps of cosiness.''

Morley: ''Does this cosiness erode the energy and

bravado of your entertainments,

or even yourself?''

Lydon: ''Only the small minded obsessed with the popular music end of things come up with those assumptions.''

Morley: ''Would inherited wealth have been a bother?''

Lydon: ''No! I'd love to have been born into a very

wealthy family. I might have ended up more marvellous than I am now.

Who knows? It's all subjective, isn't it. But who needs to suffer to

be great? Not me, thank you.''

Lydon: ''No! I'd love to have been born into a very

wealthy family. I might have ended up more marvellous than I am now.

Who knows? It's all subjective, isn't it. But who needs to suffer to

be great? Not me, thank you.''

Morley: ''This attitude you have towards things – how would you describe it?''

Lydon: ''It's smug, isn't it! At least I'm honest, unlike all the other wankers pretending they can change the world, not their world. Look, I know not everybody has the opportunity like I had to get out, but it's worth a try. For me, the Pistols helped. It fell into my lap. Through sheer gall. Yes, that's my job. Out of the way. Give it to me!''

Morley: ''I suppose you're so antagonistic towards the trivial pursuit of the pop interview – elsewhere, of course – because people want you to embrace your special past.''

Lydon: ''Yes, and there's no joy in that. Do I always

have to have people expecting me

to be Johnny Rotten? Maybe when I'm 60 and fond memories turns into

daydreams and gross exaggerations I can remember... but I see it all

very clear and I don't need to be reminded. I'd rather think about

what to do next.''

Morley: ''So the past disappears for you?''

Lydon: ''No. It's still there. I'm not running away from it. I'm just not wallowing in it. I don't need the Sex Pistols to continue. It's as simple as that. There are those that do, of course.''

Morley: ''For many it was one of the great moments, whichever way you look at it.''

Lydon: ''That's nice. What else? Am I meant

to tell lies about how wonderful it all was,

like the rest of the jaded pop wankers filofaxing their history. 'Oh,

that's really good, to be remembered and loved and wanted, it's what

I live for.' Well, it isn't. I read about things

that were supposed to have happened then, as if they're fact. Well,

they're not fact. They're fucked. Who needs to get obsessed with counting

it all out now? It was good at the time. It could have gone anywhere

at any one point. It kept people on edge. It kept me on edge, I know

that I was scared to walk down the street half the time. At the end

it was

a pointless re-running of a B movie, packed with the obvious. It shouldn't

have been.

It could have been something very courageous and an absolute change,

and yes we could have won. We could have dictated to the record companies,

so that things would be based on invention rather than convention.

Interesting things could have been done on a wide scale! But that's

the romantic in me speaking.''

Morley: ''What betrayed it?''

Lydon: ''Lack of insight from most of the participants. This isn't to make me sound like a wounded genius... but it's a shame it didn't work out completely. We could have achieved so much more! Just think... but who does? Not many...''

Morley: ''This is the year we're meant to be celebrating the 10th anniversary of punk.''

Lydon: ''Pathetic. Really dismal. It's everything I hate, loathe and despise about the world. It's sad having to look into the past to find some sort of security. That's for the Darby and Joan clubs. What are they going to do to celebrate? Fly Billy Idol in as guest of honour? Y'know, that wasn't all of my life. I'm barely 30. I've got a lot longer to live. I've got lots of things to do. I don't have to cram the whole of my existence into a year and a half. I don't want to be made to feel ashamed because of other people's obsessions and delusions...''

Morley: ''But then you've found happiness.''

Lydon: ''I think so. I've got everything I need in

Los Angeles. 50 TV channels! The sun's outside... I hate the sun, but

it's nice to know it's there... I rise at 4.30 in the afternoon.

In bed by twelve. Watch films all night.''

Morley: ''It's a life...''

Lydon: ''It's a good one, I enjoy it. I absorb culture

through my backside! That's a very trivial way of seeing me, isn't

it. It's not entirely true. I enjoy going into the studio from time

to time. I enjoy making records. But I like to give myself loads of

free time where I can

read all the books I want to read and paint all the pictures I want

to paint. I know how to satisfy my needs. I'm not the angry young man

anymore. I used to be angry about my own lack of alternatives, and

since nobody bothered to give me any I made them up for myself.''

Morley: ''Alternatives that rely on money.''

Lydon: ''Can't do it without cash. And I've got some

of that from one particular business venture or another... a lot of

it has nothing to do with the pop industry. I don't want to

talk about that. I don't think it's too good for the world to know

that I'm a real estate agent!

My private life will remain private. No one can come close. I just

don't need it.''

The man with the stiff beard is playing a Moses for pleasure, but

he'd be better off in a

St Bruno commercial. He stands firm on a man-made lump of sacking and

soil and pretrends to gain some deep and mystical rapport with the

rank and file of humanity.

It's a video shoot. The director watched Cecil B. DeMille on New Year's

Day.

The singer is less desolate than he was in the jammed car. His teeth are back in, the sly glint is returning to his eyes as if he's gulped a mouthful of firewater. Slippy sarcasm replaces flat sulk.

Lydon: ''I have a number of smeary questions to ask the director about the exact nature of this video. The religion seems to be getting slightly out of hand.''

The figure of a golden angel glows in the setting sunlight, the angel is small and bright, while the heavens turn violet and tinge into green... A complex, cute little boy extra wanders past the singer and asks his guardian: ''Was that Johnny Rotten or Vyvyan?''

The singer and the director confer about the state of the religious involvement in the video representation of the thoughtful and tender 'Rise'. The chorus of the song, ''May the road rise with you'', is an old Irish expression meaning, more or less, may your future be a brighter one.

Lydon: ''It's about South Africa. The blacks can't be subdued for much longer...''

Morley: ''A sign of concern!''

Lydon: ''OK... it's creeping out, slowly but surely.

Of course there's concern. I'd be a liar

to pretend there's not, and I'm a liar. The song is not as personal

as it could be, because I've never been to South Africa, but it can

apply to lots of other situations, myself for instance. May the road

rise for me! I still need it...''

The singer and the director have come to an understanding.

''I don't need this Biblical nonsense,'' announces Lydon. So he's prepared to mime his lines amidst swirling leaves, but cannot accept singing into the camera through a burning bush. ''If I'm expected to do that I'm afraid I will be laughing somewhat.''

As the final parts of the video are completed, it seems to swing away

from crank parody towards being simply an aggressively crooked individual

performance. The singer takes over from the props and whimsy, melodramatically

raising his own spiritual temperature.

At least that's the idea. The singer attempts to push, in his own way,

with an old fervour, the Biblical incidents to the end of the world.

Lydon: ''We'll do it my way in the end. The correct way. I'm not interested in making the video some overcomplicated piece of nonsense to achieve an entertainment. I just don't need it.''

This is the beginning of an interview with the John Lydon who used

to clean offices with Sid Vicious, and who recently ran out from a

courtroom apparently clutching a cheque for

£1 million squealing with delight ''It's mine! All mine!''

Lydon: ''Oh, that doesn't contribute to my luxury. It's really difficult to sort it all out. The tax are on our backs. It's not quite what people think, or what I led people to think...''

Morley: ''Why were you so delighted then?''

Lydon: ''Malcolm didn't get it.''

Morley: ''He's contorted with self pity, you know.''

Lydon: ''Oh, of course... it's his latest act.''

Morley: ''He says he couldn't be bothered dragging in all the witnesses to prove his case.''

Lydon: ''Any why do you think that was, what would they actually prove? What could they prove about my money being spent for so long? Obviously not a lot.''

Morley: ''He wanted to prove he did it all.''

Lydon: ''Which isn't true. Hindsight is what Malcolm suffers from. I did this, that and the other, he'll say, after the dust has settled. He did very little. Everyone else did it for him.''

Morley: ''So you wrote the lyrics to 'Anarchy In The U.K.'?''

Lydon: ''Yes...''

Morley: ''Yes?''

Lydon: ''Oh, you want an answer... Of course I did. It's stupid to dispute it. It's absurd. Julien Temple even said he wrote it. If this is the case, none of these people have exactly come up with anything similar since.''

Morley: ''And you have.''

Lydon: ''Of course. Lyrically I'm better than ever. I am a man of the pen!''

Morley: ''Has Alex Cox been in touch with you concerning his romantic film?''

Lydon: ''We met in New York. I expressed an interest in what he was up to. They'd already decided to go ahead without even contacting me.''

Morley: ''That's no big deal.''

Lydon: ''I'm still alive! I don't want to be represented

without my say so. I think that's grossly unfair. You try doing that

to Mick Jagger. See what he has to say about it.

Why should I be any different? I still haven't given my permission.

I read the first script and I thought it was revolting. It made light

of something so serious as Sid's habits... When we were touring America

I kept Sid on the bus with me where he was completely alienated from

the drug culture, and he was fine up until San Francisco – and

it might be a coincidence but as soon as Malcolm came round

to our hotel Sid hit skid row... I'd like to see how they'll deal with

that. They've got some Scouse chappy to play me. It all sounds really

sleazy and awful. Alex Cox is a very good director I think, and I think

he should know better. If he pulls this one off then he's a genius.

For my mind so far, from what I've seen,

it sounds appalling. I am the genuine article and I haven't been consulted.

It's going to become another lie. The truth was, it was awful. Absolutely

awful. Sid was very emotionally upset for all sorts of reasons, and

'cos he was a little bit naïve he did believe the image of him

that was touted in the press... I mean, he was named after my pet hamster

and a

Lou Reed song, 'Vicious, hit me with a flower', which was

Sid's style. He was as weak as they come. He was not a violent chap,

and it was quite sad to pretend to be one, to see

his slow demise, and to see people enjoy that demise. Malcolm thrived

on it. He thought that kind of destruction was what being a pop star

was all about. I hated that. We weren't meant to be pop stars. I tried

to fight that bitterly. I just didn't need it.''

Three days after the white sheets and Ten Commandments of the video

day, I begin an interview with the John Lydon who is the only great

up-to-date popular entertainer to have been influenced by Captain Beefheart,

Peter Hammill and Keith Hudson. It was the thorough pleasure Lydon

found in the playful mutants and lost beauties of rock that helped

bend the Sex Pistols beyond the blunt base of mere agonized cock-shock-rock.

He chopped in the subversive incoherence and wild sense of intimacy,

because he was drawn to the creatures of pop, not the sweet

stars. It was this side of Lydon that baffled McLaren and led him to

form one of the few intelligent, independent, sniping groups of round

about now. If anyone cares. Without being too academic, modern pop

music,

the stuff on the supermarket shelves, has been influenced by Elton

John, Bread and Squeeze, while PIL are a shrewd, dishevelled suggestion

of how it coud have been if

punk had worked out not as a supplier of picture discs and cute graphic

design, but as a splitting spread of noises and instructions inspired

by Faust, Iggy and Pere Ubu.

PIL became, in a manner of speaking, one reminder of the curiosity

and sardonic personal passion that linked Television and Patti Smith

to the better, more ingenious insides of British punk. It's something

to think about.

This is the beginning of an interview with the 'happy go lucky couldn't care less for men may come and men may go but I go on forever can't help but have fun' John Lydon, who's visiting London for a few weeks ''to do a little bit of work and shine brighter than the rest of the pop wankers, if anyone bothers to notice.'' His voice, of course, camps out somewhere between nicely dismissive and crude Carry On. Sometimes he celebrates.

Lydon: ''It's great to come back and play all the

old albums again. 'Trout Mask Replica', 'Goodbye to L.A.', 'Funhouse',

Burning Spear, loads of other, and they're still all classics.

It used to be great to go into a record shop and just buy something

because the cover was either great or dull. There was so much to discover.

Of course this way of buying led to some great blunders. Shawn Phillips

comes to mind. But that kind of curiosity and possibility just seems

obliterated these days. I'm sure kids are absolutely restless and

not just into instant access, but it's getting tighter and tighter.

There's so much routine about making records these days. Like, I like

Jim Kerr, but Simple Minds do not make classic records. They won't

stand the strain of time. 'Metal Box' will. T. Rex are better than

ever! Oh, maybe we're just old farts wallowing in memories. I'm willing

to admit that might be a part of it, but there is a relevance to remembering

how active and chancy things were...''

Morley: ''What is the point of a PIL record?''

Lydon: ''I make records for myself. I want them to

be completely precise. Accuracy is very important to me. Otherwise

it's bad work and a waste of my time, and I really don't want to waste

my time. There must be a conclusion to what you do, no vagueness. There

must be a sense of completeness. Every song is an emotion and it has

to succeed as that, otherwise you've failed. It's bad work. That annoys

me. Bad work from anyone just

annoys me. I just don't need it.''

This is the beginning of an interview with the John Lydon who is in love.

Lydon: ''I keep my private life with Nora private, but I'm very proud of our love. That will hold with a full stop. I will not celebrate. I don't think I need to. You can't describe these emotions to people until you've actually experienced them yourself, and I don't think silly love songs will achieve that. It's a surprise to me that I'm in love. To me that's an advancement of my character as a really good human being. That I understand what it is. It's not the clichéd crap you're led to believe it is at 16. All you youngsters out there are going to have to wait to find out. First of all you're going to have to be angry just like I was!''

Morley: ''Are you just easing through the natural stages of growing up, mellowing and all that?''

Lydon: ''I suppose I've got a lot of the things I

want out of life, and my needs and requirements are very minimal. I'm

a cosy little chap and I'm very smug about it. I know

a lot of people who read that will hate me for it, but that's because

they haven't worked it out for themselves. Well, patience.''

Morley: ''Have you become a kind of connoisseur?''

Lydon: ''I've become specific. I know how the seperate the gunk out of everything and get the best out of things. You can't absorb everything like a sponge! Oh, it's awful, sounding like an old tosser...''

Morley: ''Are you going to have children?''

Lydon: ''I wouldn't want to bring anyone into this appalling state of affairs. They might be weaker than me and not able to cope. I'm not capable of looking after them. It would be too unfair on them to have me as a father. It's too much of a burden. And there's enough people in this world as it is. Orphans I feel sorry for. Maybe I'll adopt... a better lifestyle!''

Morley: ''Is your selfishness your success?''

Lydon: ''Yes. Isn't it wonderful? But isn't everybody selfish? They should just admit it. What are they hiding from? Hehehehehe. The world's going to hate me... again.''

Morley: ''Who cares about you?''

Lydon: ''Everyone and no one. Who cares? I just don't need it.''

This is the end of the interview with the consummately self-satisfied John Lydon, who was 30 years old on January 31st.

Lydon: ''Once I was scared of reaching 21, let alone 30. But now I feel 'So what?' I've got at least 40 more years before I call it a day, and I mean to use them all up, they're all I've got. I'm 30 and it doesn't matter. Water off a duck's back. Here's looking at 40, kiddo.''

Morley: ''It looks like the end of the interview.''

Lydon: ''The end?''

Morley: ''We've been through most things: laziness, indulgence, confidence, love, evil, impatience, and I won't mention the smegma or the film. We've seen you as spoilt brat, elder wiseman, prince of reason, we've gone back as much as possible and performed wonders with the future. The present came and went. I think it's the end.''

Lydon: ''The end? Of my interview? The end??? I just don't need it.''

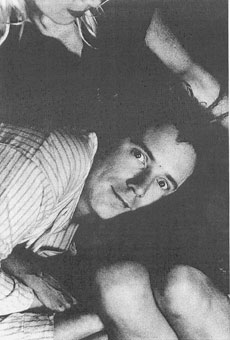

![]()

© Anton Corbijn 1986