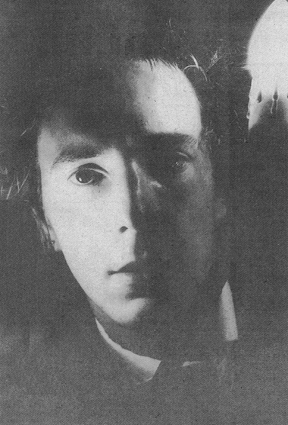

John Lydon and Keith Levene:

Melody Maker, March 14th, 1981

Transcribed (and additional info) by Karsten Roekens

© 1981 Paolo Hewitt / Melody Maker

REMAIN IN LIGHT

The Public Image interview by Paolo Hewitt. Pix: Tom Sheehan.

Anything but rock music. Anything but that lumbering, old-fashioned creature which has been alive ten years too long now. Something that is new and exciting. Something open and provocative. No backtracking. Innovate don't imitate. Lead don't follow and damn those dumb whispers and accusations. We don't care! No strings leading off your back and no one pulling. Your actions. Your beliefs. Your way. The only way.

Anything but rock music. Anything but that lumbering, old-fashioned creature which has been alive ten years too long now. Something that is new and exciting. Something open and provocative. No backtracking. Innovate don't imitate. Lead don't follow and damn those dumb whispers and accusations. We don't care! No strings leading off your back and no one pulling. Your actions. Your beliefs. Your way. The only way.

Such have been the ideas and ambitions of Public Image Ltd., and that's Public Image the Company, and not Public Image the band.

For three years now Public Image, at present three individuals by the name of Keith Levene, Jeannette Lee and John Lydon, have been busy creating, and then following, their own self-appointed paths. In doing so they've created music that is looked upon as pure junk by some, and breathtaking by others. It has provoked, antagonised and demanded more from people than one would normally expect.

As a guideline to it, its detractors constantly point to the previous career of the singer, John Lydon, as a member of the most crucial band of the '70s, the Sex Pistols, and ask why he hasn't continued to champion the sense of outrage that once provoked people to attempt to carve his face up in car parks. Betrayal! Treason! He's doing everything the Pistols set out to destroy, meaning self-indulgent, irrelevant music. His actions along with the rest of the company have divided as much as they have united, confused as much as clarified. They're taking the piss! Which way are you looking?

It's not only the music that gets up the public's collective nose. The Company itself has constantly refused to fall into rock's everyday regular routines of albums and tours, middlemen and the easy way out. To do this PIL has had to become, like Dexy's (whom Lydon believes to be nothing more than an "arrogant stance" with nothing to back it up), isolated from the mainstream of rock bands, to ensure they stay en route. The hard way maybe, but in truth the only way.

Now there's a fourth album ready for release. Called 'Flowers Of Romance', the first I hear of it is in a car on the way to meet the Company at Jeannette Lee's house.

As usual it's unlike anything you've heard before, either from them or anyone else. Drums smash into your system with an unbelievable vengeance, set viciously upfront next to Lydon's unique vocals. The bass, normally so important in PIL music, is nowhere to be heard. The same with the guitar. Bagpipes and a Balinese instrument called the Bahlain [1] all contribute however. It has form, it remains as provocative and as challenging as ever.

Believe it or not, Public Image have got stronger, harder than the rest. Or, if you so inclined, more irrelevant, more pathetically indulgent. And so it goes. But this writer knows where he's going, and his card is still firmly marked in favour of PIL.

Rock music, apart from a few exceptions, is slowly dying on its feet and no one wants to admit that. They'd rather hand you over comic book bands who are either cretins, or who are dangerously cretinous (as in fascists) and unbelievably enough get support from a small selection of punters, press and music business. Rock music is in a disgusting state. It's pointless to name these people (we haven't got six months), but if rock music is to change, remain vital and vibrant, something that becomes a part of your life, then 95% of all known rock bands better start arranging their wills now.

But then, what do I care? These days Linx, Kleeer, Light Of The World and The Supremes hold more interest for me, seeing as how nearly every other band has lost complete sight and vision as to what they're about and why they're there in the first place.

Public Image remain in light, though. Same as they ever were, and look at me! Sitting in a sitting room with John, Keith and Jeannette. The Flowers Of Romance indeed. Like their music, Public Image treat everything with a startling frankness. They have to. They can't bring themselves to trust anyone. They have to be wary, find out about people's motives. In the sitting room Keith Levene, after ten minutes or so of casual questions and answers, decides to find out about mine.

As with all interviews with people you've never met before, indeed with all conversations with strangers, the talk starts off casually. Lydon had said that the new album had only taken three weeks to complete and that Public Image had never been stronger. Ideas to expand into other fields like film and video were still very much alive, and that Public Image "do things to the best of our ability, which is usually a hundred thousand light years ahead of everybody else."

I was just about to ask what other plans were afoot when Levene suddenly butted in.

"I'm finding it really hard to do interviews," he said, his voice desperation itself. "I really don't like the questions. I think they're weedy and horrible."

Taken aback a bit, I ask him what he'd rather talk about. He turns on me angrily.

"You're not interested in PIL, are you?" he challenges.

Yes, I reply calmly, or else I wouldn't be here.

"Are you sure? It's not the situation that PIL have got a new album out, and you're the 'Melody Maker'? You see, if I'm interested in someone, like I used to be interested in Eno, I know what I would have wanted to talk to him about. I know what I would have said to him because I had an insight into what he was doing. And that's really hard, you know? It's very, very difficult to talk about what you're doing unless somebody is interested, and that's how I feel about it. It makes it very hard. That's why I asked you, are you interested? Because if you are you must know about us. You must know what we've done."

Levene shakes his head in despair. Next to me on the sofa Lydon keeps disturbingly quiet.

"My brain is fucked at the moment," Keith continues, "and I don't want to talk. But we've got to do this interview."

The fact that I'd been trying to set up this interview for the last three months doesn't seem to phase Keith too much. And anyway, what's all this 'got to do an interview'? I thought the whole thing about PIL was that you didn't have to do anything?

"Oh, all right!" Keith explodes. "I mean, fuck off! I'm obliging Keith." (Broughton, a Virgin press officer) "Keith said this interview is at four today, and here you are. I could leave it for a month, saying 'Oh, I don't actually feel like doing it right now.' But that's a load of bullshit, saying one of PIL's things is that we do what we want – we chose to do the interview! Did you think about this interview before you came in?" he sneers at me. "What did you think about?"

I tell him that like all other interviews I do there's not much point going straight in with explosive questions, which rely on some kind of established rapport between interviewer and interviewee for a satisfactory answer. Hence the general questions at the beginning. But if that's the way you want it – what do you think about your music described as nothing more than a general piss-take, worthless rubbish you're all hiding behind?

"Well, that's whose ever accusation," Keith replies a bit calmer. "People were scared to like us, right? They didn't know whether the record was a piss-take or whether it was serious. Well, as far as I'm concerned that doesn't matter. If they think a record is good, whether it's a piss-take or not, they should like it if they like it. And if they don't like it then that's their hang-up. They shouldn't worry whether we're taking the piss or not, or whether we aren't. As it happens we're very serious, right? Musically we're just trying to do things that haven't been done before. We're sick of ..."

Levene breaks off.

Levene breaks off.

"Look, you know all this. You know what we think of music. We're sick of the crap that follows us and the general crap that is around at the moment and the crap that's in the charts. We're just trying to do something good, something worth listening to, something worth going out to buy an album for. I used to buy an album at least once a week, or nick an album once a week. Now I've no interest in albums."

He means it, man.

"I got into collecting records when I was, say, 14 or 15. At the time I was learning how to play guitar and I was buying things like Johnny Winter, the Allman Brothers, John McLaughlin. I knew about Cream, I knew about Deep Purple, the whole general stuff that was about at the time. I was into the whole scope of it. I used to buy the odd reggae thing too, 'Club 67' ..."

Keith Levene has been involved in music for a long time, either playing or listening avidly to it. These days he does neither.

"My favourite band at one time for about a year was Yes. Steve Howe was my favourite guitarist. I actually roadied for him on one tour, that's what put me off, but he still remains one of my favourite guitarists, you know." [2]

After a year of listening to people like Howe and religiously practising his scales every day, Levene suddenly got very good on the guitar. He could play anything he turned his ear to, from free to jazz rock. [3] And so, subsequently, just before he met Bernie Rhodes he got very bored with it.

"I met a bloke called Bernie Rhodes, who I think is a great, important person, and it was him who made me think a lot. Bernie would challenge me all the time. Whereas a lot of people would think 'Oh great, I'm in a band and I'm doing it!', Bernie would challenge lots of things. Like, what is my motivation for doing it, and so on. I went through a very heavy trip of questioning this and challenging that. Now I can laugh at it, at the time it was very serious. But it did give me a kind of 360 degrees scope in the end, instead of a blinkered way of looking at things."

It was round about this crucial period of developing the technique and attitude that has become such a crucial element in the music of Public Image, that Levene first met Johnny Rotten on tour in Sheffield. The Clash were supporting the Pistols and both musicians had found themselves ostracised by their respective bands. [4]

"I was sitting on my own over there and he was sitting on his own here. I said hello. But I left The Clash because it was either me or Mick Jones, and it had to be me because if I stayed with them all the rest would have had to have left anyway. Joe Strummer is a great bloke and all that, but he's very kind of vulnerable. Anything I suggested they really looked at me as if I was mad. I could have stayed with them and shut up, which is what a lot of other people do, but I didn't."

Just as Levene was having his problems, so the charismatic Rotten, who from the outside seemed to be succeeding so well in his bid to destroy both rock and establishment (Bill Grundy and Bob Harris, where are you now?), was suffering similar problems.

"When we started," says Rotten in those clipped measured tones of his, with that glorious edge of sarcasm clearly detectable, "no one could play anything, and that was great. A glorious din. But in the studio, I'm afraid, they took it serious. I mean, Fatty would lay down twenty-one guitar solos. That was nauseous, that pissed me off. I didn't like the sound of that album. Well old-fashioned, well easy. I was given one go at each vocal, and I swore never again would anyone have that much power over me and tell me what I should be doing. The rest of them just liked it that way and didn't like the new songs I was writing. I wrote 'Religion' in the Pistols, and they wouldn't touch it. But then again they wouldn't touch 'God Save The Queen', or 'Anarchy', come to that. They had a very retarded, suburban way of looking at things. You see, I'm quite happy to sit down and listen to Patagonian flute music, but to get the rest of them to understand that is an impossibility. And it all came to head in America and that was the end of that. See, I always thought the Pistols were going to be the end of rock 'n' roll, you know? This is it, killing it off. But ..."

Instead a whole host of imitators followed while Rotten joined up with Levene and bassist Jah Wobble and drummer Jim Walker, to produce PIL's startling debut album. Ironically enough, the very people who'd stood on a stage for the first time because of Rotten slagged off his new direction mercilessly, completely missing the spirit of the music that coincided so perfectly with punk's original aims.

"I just felt the same way as John did when PIL formed," says Levene. "No producer, no manager, no ridiculous middlemen, and that's how we started. We didn't realise what it would mean. We didn't realise that between us we would be able to run a studio, which we can now, and between the three of us deal with corporation tax and VAT, who nearly had the company closed down. In other words, instead of being in a group, doing your gig and doing your tour and having your producer tell you what to do, and you're not doing anything that Pete Townshend didn't do ten years ago, we were kind of breaking new ground, a lot of new ground. And especially with the sound that we were coming out with."

Which is more than correct. I can remember clearly standing transfixed in a Kentish Town record shop listening to advance copies of that debut album and having my breath taken away by its power, audacity and disturbing qualities. Of course the band never toured with the damn thing. They just retreated into hiding or wherever they went, and emerged with a new record, contained in a Metal Box. Over six sides of vinyl the band had moved ahead again, placing the bass as the single most important instrument and, as in many disco and funk records, letting that along with the drums do all the talking.

"Metal Box was never intended to be listened to all in one go," says Keith. "It was just a load of material from PIL in a Metal Box. I mean, you couldn't listen to it all in one go, it was just a load of singles – play one side, play two sides. You see, we had this meeting with Virgin and they said 'Yeah, but people are going to have to keep getting up from their chairs and turning it over.' And I said 'No, it's not like that. They're not going to be listening to it as an album.' The idea is that they've got a load of material from PIL which they can listen to when they want. I mean, I couldn't listen to it all in one go!"

After the album's appearance and the usual amount of controversy, PIL, who had already been through three drummers plus a disastrous tour of the States, suddenly found themselves without a bass player when Jah Wobble decided enough was enough and upped and left.

"People don't leave Public Image," corrects Keith, "they are asked to leave."

"He was just heading in a different direction to everybody else," says Jeannette.

And that's all there is to say. So then there were three, and they've now produced their fourth album, the third being the wonderfully funny 'Paris Au Printemps' album, a live collection from France, designed to beat the bootlegs that have been flooding the market in the absence of Public Image live performances. Hear it, but also hear 'Flowers Of Romance' as well.

On first hearing it seemed even more intimidating than its predecessors, though the notion that PIL music is 'difficult' is nonsense. It's probably some of the easiest music available. 'Romance' relies heavily upon drums, which provokes the disturbing thought that PIL might actually be following musical trends instead of leading them. What with the likes of the Ants and Bow Wow Wow crashing their way round the charts?

"Yeah, it's coincidental I tell you," says Keith, sounding just a mite pissed off. "I was onto it, believe you me. If you'd listened to any of my previous conversations to do with music in the last six months, it was always down to that drum sound. Always. Always. And the first thing that emerged from it was the first track you heard today, because in the end I ended up doing that on my own. [5] And that did set a lot of the feel for the album. It happens to be the in-thing at the moment, but it annoys me."

Lydon also feels the same way.

"If you're talking about din like Adam & The Ants," he sneers, "then there's no comparison. They need two drummers to make such a weedy, poxy, insipid sound!"

He laughs at the thought, and I throw out a question about his lyrics. Was there any meaning behind the moaning, or just drivel?

"They're specific subjects about things I know about," he replies. "No waffling or going into politics. Domestic scenes." He laughs. "And that's about it. That's what they're about."

"It's a drag," interjects Keith," having to specify what they're about. I don't like that. I don't think it's interesting."

"And it's always minimal what I write," returns John.

"The most amount of things in the least amount of words," says Keith.

As for my notion about the music being less accessible, forget it.

"Less accessible?" questions Keith. "You'll find that it's not. It's just very intense. It's more accessible actually because it's a much clearer sound, and I think that's really good because otherwise you find that like listening to the radio. It's background music, easy to listen to. This you can live your life through it, with it. It's more intense. More levels, more depth to draw on."

"We mean what we do," says John from the other side of the room. "And if that threatens Joe Bloggs then that's too bad."

"It's not for Joe Bloggs then," Keith puts in quietly.

On the other hand, I argue, Joe Bloggs could quite easily accuse PIL of being talentless idiots who have been lucky enough to gain access to a studio, and why should he waste his time on you? Jeannette answers.

"Perhaps it is a load of nonsense to some people, and I'm sure it is. But that doesn't make any difference."

So I could go into a studio and create rubbish and hide it behind a statement saying 'I'm not responsible'?

"Yes," John says excitedly. "What's wrong with that? I thought the whole idea was to get people into studios and do it themselves."

"We're not anything elite, you know?" Keith explains. "We're nothing special. That's why we don't do gigs. My reason for not doing gigs and my reason for wanting our music to go with film soundtracks is because I hate the idea of saying 'Well, we're in a group, and aren't we great? We've been into the studio and made this album, and now we are playing it and you should look at us and buy this album and also think we're great!' It's not that at all. I find it embarrassing on stage, you know? I felt embarrassed because these people seem to be placing themselves in a non-entity position, looking up to us. And I don't want them to do that, I want them to realise that they could do it if they want."

John nods his head in agreement.

"Anyone can make records. Whether they're good or bad is up to the public. But I think everyone should have a go at it, and they should do it themselves."

The suggestion that PIL are the new Yes or Genesis holds no water then?

"I see no PAs," laughs Lydon. "I see no snob hippie attitudes to the world. We're not claiming ourselves as virtuoso musicians or any of that old toss. We're doing what we want. I think bands like Yes or Pink Floyd make records that they know will please their public. Bands like that are enemies of mine," he says, his tone quickly changing into one of sullen anger. "They really are retards. They're not achieving anything. They've got all that equipment and all that money, and they do sod all. They stay in their own narrow-minded, whimsical, little pathetic ways and never ever improve themselves or other people. You go and see any of those bands and you get exactly what you expect. That isn't entertainment."

Would he say PIL were entertainment though?

"Yes, I think we're very entertaining, thank you very much. Variety is the spice of life and all that. We're not claiming that the world suddenly drop all their attitudes and ideas and slavishly adore us, you need variety. The charts should be infinitely variable, that is essential. I care about what we're doing. I don't like what a lot of other people do, I still do not deny them the right to do it, though."

"If it doesn't interest me," agrees Keith, "then I won't care for it. I don't care for DLT or Nicky Horne or the way the whole thing is run. I think it's all a load of bollocks. It makes me ill, old ladies deciding where some records are going to be in the charts. I don't expect to get into the charts.I'd be insulted if we got to a number one position. Which makes things very hard for us."

But then, life for Public Image was always going to be hard. When they formed the Company no set roles were allotted to anybody. Jeannette (whose portrait adorns the new album sleeve) for instance has no defined role apart from being Jeannette. She doesn't play any instruments for instance, but she is as important as John or Keith. Similarly the band, sorry, Company see themselves as pioneers, but not only in the music field.

"We all know about what we don't want," explains Keith. "We've got very similar views about things and can see the difference between The Clash's bullshit and the government – for some reason I always think of The Clash and the government as something similar – and it is going to take time. It's going to take a long time because we're involved in these other fields. We're involved in video and we're involved in electronics. Like, all these Japanese people came round John's flat one day. They were from a magazine and they just wanted our sound system. They had heard we had a great sound system with a lot of stuff and it was great. All we wanted was a mention, fuck the group, just 'Public Image are aware of technology', 'Public Image means technology', anything. I mean, I wanted a grant from Sony for developing proper videos, and I wish we could have developed. It's very hard talking to Japanese people."

He laughs.

"But that excites me and interests me more. Getting an advance from ICI is more up my street than getting an advance from Virgin. We've got certain commitments which will run out in a year and a half, and that will be the perfect timing for what we want to do. One of my minor ambitions in PIL is, I would really like it to market sound systems and videos. Good ones. You know, how the WASP is the cheapest accessible synthesizer? We want to put videos at that level and sell them."

The only hindrance to all these plans, it transpires, is naturally enough a lack of finance. Especially when they're still involved in various court cases like John's recent Mountjoy trial and the run-in with McLaren to pay for. Naturally enough in these days of Thatcherism, John is also receiving nothing from the Pistols industry that has sprang up over the last two years. No money from badges, books or 'The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle' film.

"The first thirty seconds frightened the life out of me," admits John about the film. "I thought, ah no, it's going to be a really good movie!"

As for touring and the like, thee's no change there.

"I think you're more honest sending a video round of the band playing," remarks Keith. "But I think we're succeeding. I couldn't define a successful situation for PIL, but sometimes a situation comes along and you have to step back a bit and see it through, time your moves and so on. I think if we pull our fingers out and make the right moves at the right time, I think we'll be more successful. It's going to take a long time, it's going to take a lot of money. I'm just trying to make more accessibility, more things available. It means that many more groups, if I ever get this system, will be able to make movies, be able to communicate, get their thing shown, whatever, through this system. It may look very happy but it's not a selfish thing, I promise. It's like when we go into a studio, if we haven't done anything for a day, it costs us a thousand quid to do nothing. We're not in that sort of position to go round making piss-take albums. We do take it very seriosly!"

I nod my head in agreement and he looks down at the silent tape.

"Have you got enough for your interview now?" he says.

Out of all the words and sentences that were passed that day, one stood out like a sore thumb. It came from John Lydon.

"As a band," he said, "the Pistols opened doors, and I walked through quite a few of them. It's just a shame that most people haven't got that far."

Beneath it all I think Public Image care a lot more than they're given credit for. Which is a strange thing to finish on. Who wants to care about music? I mean anything but rock. Right?

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The instrument is actually called Angklung (used on 'Hymie's Him' and 'Pied Piper'). Bagpipes were not used on the album.

[2] According to his 2001 Perfect Sound Forever interview, 16-year-old Levene approached Yes at their five concerts at the Rainbow Theatre (20-24 November 1973) for a job and joined them on their subsequent UK tour (which ended on 10 December 1973) as an assistant of drummer Alan White's roadie Robert 'Nunu' Whiting. He again tried to help out at Rick Wakeman's Royal Festival Hall concert (18 January 1974), but Wakeman told him he was useless as a roadie.

[3] In 1975 Levene tried to get into Ultravox when he was sharing a flat with their drummer Warren Cann near Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in Friern Barnet, London N11. Warren Cann: "He was a guitarist and had heard some of our rehearsal tapes. He kept pestering me to join the band - 'C'mon! I'm a much better guitarist than your guy!' I'd say 'Listen, Keith ... all you ever listen to is all that fucking widdly-widdly jazz rock Frank Zappa/Todd Rundgren Utopia crap… Forget It!'" (Electrogarden.com, 2002)

[4] The Black Swan in Sheffield (4 July 1976), now The Boardwalk.

[5] 'Hymie's Him'

![]()

© Tom Sheehan