Bass Cultural Vibrations:

Visionaries, Outlaws, Mystics and Chanters

First

Published 3am Magazine, October 2002

© 2002 Greg Whitfield

This expanded version republished Fodderstompf, October 2002

Fodderstompf: In this extensive article Greg Whitfield covers the origins of the Dub / Punk crossover from Jamaica to London. PiL and their entourage feature heavily throughout; along with the likes of Jah Shaka, Adrian Sherwood and Lee Perry, and bringing the story up to date with London's Disciples and More Rockers.

The whole article comes from a fresh perspective, and doesn't simply retread the usual "punky-reggae party" bollocks. For example, among the 'PiL' subjects covered are John's trip to Jamaica, The Steel Leg EP, and the often ignored PiL / On-U-Sound crossover. PiL / Dub fans will love it…

The vision dreamt by King Tubby in Kingston Jamaica, to shaking the foundations in London, with Jah Shaka, Don Letts and John Lydon...

By Greg Whitfield

"The

drum represents the heart beat; the bass is the thought, a line that

flies. Walking bass, talking bass, comes from the brain."

Lee Perry, Black Ark Studios

"Shaka

lets the weight go BOOM! The crowd succumb to the beat and abandon their

souls to rapture at the hands of Shaka, the drum and the bass is transformed

into a huge aural purge of sound thundering around the room. Shaka is

at the controls like a man possessed the bass growls, a physical presence.

Dancers cavort and frolic, never missing a step. Shaka weaves his spiritual

spell, urging the faithful on to further displays of terpsichorean excess.

Whip them Shaka! someone cries. This is Jah Shaka, King Of The Zulu

Tribe in session!"

Disciples,

after witnessing the mighty Jah Shaka in sound system session, London

From

the explorations of UK punks into the Avant Garde possibilities in music,

onto John Rotten's trip to Jamaica, after the demise of the Sex Pistols,

and onto his explorations in Public Image with Jah Wobble, to Jah Shaka's

other worldly spiritual devotions and sound system dances. This is where

the roots of this British spiritual dub journey begin.

From

the explorations of UK punks into the Avant Garde possibilities in music,

onto John Rotten's trip to Jamaica, after the demise of the Sex Pistols,

and onto his explorations in Public Image with Jah Wobble, to Jah Shaka's

other worldly spiritual devotions and sound system dances. This is where

the roots of this British spiritual dub journey begin.

Bass, bass and drums. As Winston Rodney intoned in an early Studio One roots chant, I n I , Son of The Most High, JAH RASTAFARI, whose hearts shall beat and correspond in one harmony, sounds from the Burning Spear! Bunny Wailer of Bob Marley's legendary Wailers, claimed that this deeply dread riddim, the unifying of a dread bass and drum physically felt rather than heard, was a bass vibration that had been set in motion at the time of creation, and resonated onwards, like a heartbeat, primal and compelling. The vibration had echoed from source, from creation. From that time onward: Weaving its mysticism, its physical, gnostic spell.

Meanwhile in late 70's England, when music had reached an all time low, punks sought out new musical landscapes, which were challenging and fresh, offering something original, some spatial and temporal experience perhaps not heard before. This was the demand of early punks, almost a musical cultural year zero. In the Roxy, one of the few London clubs which actually allowed punks a place to play, one Don Letts, Rasta and an early, agent provocateur, having been one of the founders of Acme Attractions and its later incarnation Boy on King's Road (Both of these had emerged out of the same scene as Malcolm Mclaren‚s and Vivienne Westwood's Sex and Seditionaries shops) and now a respected film maker, started to play early roots and culture music. Why? Because it was a punk club, yet there were only a handful of punk records that had been made!

Don Letts explains it this way, "There just weren't many punk records to play! I played some early Detroit music like the MC5, The Stooges, then Captain Beefheart, The Saints, really heavy and freaky garage punk tunes like that. But there still wasn't enough music to play, so I thought I'd play them my music, music I loved, and that was hard dub music. This was MY thing you know, and the punks loved it. And they loved the drugs too! We used to roll spliffs for them I had my simple DJ set up, nothing like the superstar DJ's you have now. I had just one little turntable, my tunes and a lot of spliffs! Punks could tune in to the righteous and dread rejection of society present in roots rebel rock, and the roaring avant garde noise which was the sound of the new emerging bass sounds from Jamaica".

In the record stores across London's black areas, people would congregate to buy up the latest 45's on import direct from Jamaica. Young punks were soon rubbing shoulders with the Jamaicans, checking out the newest Prince Far I tunes. When you dropped the needle on a version side of a roots and culture 45, no one really knew what to expect. At the time, and even now, the sound was awesome, eerie, a bizarre experience, the needle dropped on the crackling and hissing plastic. Orthodox, even conservative drum patterns announced the start of the track but from then one was cast in to uncharted territory, an unknown space, sirens shrieked, voices cut in and out, cut up, disembodied, shredded, played backwards, with shattering echo. Suddenly, a horn refrain might drop in to the mix, regal, yet harsh like sheet metal, a wall of sound. Dropping in, stepping to the riddim, keeping time. Brittle African percussion and sparkling, impossibly trebly hi hat, spreading circles of sound, spiralling through the space created by the sound engineer, a sonorous echo chamber.

Nothing quite like this had been done before, then suddenly, just as one got ones bearings, the whole track seemed to be ripped out from beneath you, and scrambled and rewound to the start of the track. Whole segments of instrumentation just seemed to appear and disappear at the whim of the engineer, then the bass, that primal underpinning, keeping the whole giddy noise grounded would drop in to the mix, and you‚d feel it in your abdomen, threatening to re arrange and pummel your internal organs, or if played loud enough, it felt like a wind, literally, punctuated by eerie shards of searing guitar, and melancholy piano, which seemed to invite the mind to a deep and cavernous space, a sad and lonely place of lost chances, memory, or at other times an optimistic, positive spiritual uplift, resolute and strong.

Listening to Augustus Pablo, it seems as if it was recorded in a cavernous valley rather than a small studio in the heat and ghettos of Kingston, so DEEP is the sound and experience. Curly B, London reggae selector and DJ, expresses it this way, "Sound System talk to you, so you go into a kind of vision. You see stars them time inna dance. The great Jah Shaka when you listen to those sounds, you can have most problems, you can have no money, but them man deh, convert your heart". This is a spiritual force, evoking the powers of nature within the inner cities of London, seeking out primal influence and modes of expression from the immediate environment. Jah Shaka explains the weaving spell power of bass culture, "In Africa, you might have 200 people drumming all at the same time. Certain sounds I use, they're really the sounds of the jungle, like birds and noises you would hear in the wilderness."

Such is the spiritual power of sound system. This was a sound seemingly completely existing within its own dimension, on its own terms, with almost no references to what had gone before, beyond a cursory nod to musical convention and tradition, teasing the listener with the apparently normal structure of a song, before whipping the carpet out from beneath the listener, as form and structure was turned on its head, as the vinyl spun round. The lyrics provided a stoic and righteous upliftment, which was deep in its meditations, offering a positive step forward to the listener, a gnostic journey considered by its devotees to be as strong and vital as the psalms of King David, from which a great deal of their inspiration was borne. King David was the author of many of the spiritual psalms, songs of profound spiritual and emotional longing, longing to reach Zion, to be free from the shackles of the corporeal form, and to attain one ness with the creator. King David was a musician, a dancer, chanting praise to God, and as such was deeply revered in Ethiopia, where it is also considered Haille Sellassie is the direct descendant of King David, who is considered by some to be from the same lineage as Jesus Christ.

This powerful heritage and imagery was not lost on the Rastas, both in Jamaica and UK who named a special style of totally committed and spiritually up lifting music after King David. King David's music as played out by the sound systems, was and is, music of the highest meditative order, in which the listener could cleanse his heart and mind, through a gnostic, sometimes shamanic experience, the experience of sound system upliftment. This is the music as message, the sound system selector (or in modern parlance, the DJ) acting as a kind of modern day urban griot, chanting and praising, inviting the listener onward, drawing him in to the musical storm. John Masouri of Black Echoes encapsulates the intense Shaka warrior experience in the following words, "To see Shaka himself transfixed; the flailing dancers pulled trance like ever closer to the eye of the storm (where tranquillity lies) is to witness one of the great British reggae institutions at it's source".

As

Jah Shaka himself expresses it in an interview with fellow sound system

operator, Jah Warrior, "Some people might dream mentally, but

I get my dreams through my ears, it's heartbeat music. So, this is music

and lyric to match some of the mightiest poetic texts, or texts of religious

inspiration". The mighty Zulu warrior and London sound system

operator Jah Shaka can still be heard chanting in his all night dances,

as he drops the needle on a crackling dub plate, "This one is

inna King David Style, so give thanks and praise to the most high..."

As

Jah Shaka himself expresses it in an interview with fellow sound system

operator, Jah Warrior, "Some people might dream mentally, but

I get my dreams through my ears, it's heartbeat music. So, this is music

and lyric to match some of the mightiest poetic texts, or texts of religious

inspiration". The mighty Zulu warrior and London sound system

operator Jah Shaka can still be heard chanting in his all night dances,

as he drops the needle on a crackling dub plate, "This one is

inna King David Style, so give thanks and praise to the most high..."

Expressing his admiration for the mighty Jah Shaka, Adrian ONU sound Sherwood puts it very simply, "I have ultimate respect for the man Jah Shaka. Shaka just loves his music, you know? He is a soul head; he knows his jazz too, deeply. Shaka just has his own thing altogether, do you understand? Playing music for ten, twelve hours without a break, until he enters a trance like state, then he's on God's plane, following God's plan".

Don Letts repeats the same sentiments, "Massive respect going out to the man Jah Shaka! You know it's interesting to see how much things have changed! In 1976, or 1977, the only white people you'd see in a Jah Shaka dance would be John Lydon, The Sex Pistols and their entourage, their inner circle, along with the Clash. These were my close friends that I'd taken with me to the dance but now, Shaka is still moving forward, taking his vibes to the people. When you check out Shaka now some twenty five years or so later in 2002, there's the French posse, the Italian posse along with the South London posse, the West London posse. It's great".

Around the time of his DJ-ing sessions at The Roxy, Don Letts turned his hand to recording, but not without controversy. He had been approached by Keith Levene, ex Flowers Of Romance, now Public Image, and Jah Wobble ( Whitechapel hard man, Blake-ian mystic, eccentric, avant garde musician, seismic dub bass addict, depending on which incarnation takes him!), to work on a dub track to be released on the 1978 'Steel Leg V's The Electric Dread' EP. Don has bittersweet memories of that session, mixed feelings, and he recounts it this way, "I remember that session to be rushed and chaotic. Keith and Jah Wobble needed some money I think, so we went down to this studio. Whilst Keith and Wobble were working on this dub rhythm, I was just sitting on the stairs scribbling down some ideas, then they just got me in and we did it straight off there and then. There was definitely some controversy amongst some Dreads who didn't think I should be writing lyrics like that (the lyrics questioned a return to Africa and following Sellassie), and Keith and Wobble really didn't fully appreciate what I was doing with those lyrics, because no two ways about it, I was sticking my neck out there, going out on a limb, and I don‚t think they could understand the full implication of those lyrics. There was no way I was intending to be heretical though, basically I was sayin, here I am, a young British Dread, and I ain't going nowhere mate! I'm not leaving. England is my home, you get me? I'd always been the Rebel Dread though; I mean I was the Rasta man who got kicked out of the Twelve Tribes of Israel for taking Ari Upp to a spiritual meeting and sharing the herb Chalice with her".

The

track itself was powerful, a dark and threatening bass booming, audibly

deep enough for the bass signal to threaten to "break up", with

Keith Levene's eerie keyboard patterns floating over the murky surface.

To Don Letts, "Jah Wobble is THE man from Whitechapel, major

respect going out to Jah Wobble! Wobble is just the man, and he was

always more down to earth than a lot of the guys on the early punk

scene, and he was there, right from the start. He was never as pretentious

or affected as a lot of those people at that time. One thing Wobble

said which has always stayed with me, he said, You have to stand

firm as a rock in this life, firm as a fuckin tree man! You know

what? The man is RIGHT, and that vibe, that attitude is reflected

in his heavy bass lines! Wobble is what I call a natural, an organic

person, and again, that is reflected in his basslines Wobble has

a strong grasp on technology, but everything he does musically has

an overriding organic or natural vibe. That's my take on Wobble".

The

track itself was powerful, a dark and threatening bass booming, audibly

deep enough for the bass signal to threaten to "break up", with

Keith Levene's eerie keyboard patterns floating over the murky surface.

To Don Letts, "Jah Wobble is THE man from Whitechapel, major

respect going out to Jah Wobble! Wobble is just the man, and he was

always more down to earth than a lot of the guys on the early punk

scene, and he was there, right from the start. He was never as pretentious

or affected as a lot of those people at that time. One thing Wobble

said which has always stayed with me, he said, You have to stand

firm as a rock in this life, firm as a fuckin tree man! You know

what? The man is RIGHT, and that vibe, that attitude is reflected

in his heavy bass lines! Wobble is what I call a natural, an organic

person, and again, that is reflected in his basslines Wobble has

a strong grasp on technology, but everything he does musically has

an overriding organic or natural vibe. That's my take on Wobble".

One of Letts first video direction/film making jobs was working on the video for Public Image's first single, "Yeah, I'm proud of that work. Working with Keith, John and Wobble was always a tense, strained thing, they were just so volatile, but that was fine, it produced its own vibe. And it was so fucking dark! They liked everything to be dimly lit and dark, so you just got this powerful impression. Wobble used to make me laugh cos he liked to sit on a fucking chair!

This avant garde mantle was taken up and extended into further unknown territory by ONU sound maestro, East ender Adrian Sherwood, who delved deeper by fusing his musical imaginings and fevered dreams with Sugar Hill Gang funk agent provocateurs (Creators of Grandmaster Flash's urban apocalyptic rhythm, 'The Message', and Keith Le Blanc's truly groundbreaking Tommy Boy 12" 'Malcolm X'), members of the legendary visionaries and originators of radical rap ,The Last Poets, and assorted ex punks drawn from the Sex Pistols and Public Image entourage, and the cream of UK's reggae and dub talents. He moulded these extraordinary new forms from Kingston, quite un self consciously, with Beat writer William Burroughs cut up techniques, and his own unique sound explorations.

In

Adrian Sherwood's words,"I was so inspired by the sheer amount

of innovative influences around me at that time. I was working with

Japanese musicians (Kishi, his wife who contributed eerie keyboards,

and classical far eastern instrumentation), then there were the African

musicians I met through Bonjo I (African Head Charge percussionist)

and it was then I met Mark Stewart, (ex Pop Group singer, and from Mark

Stewart and The Mafia, using the line up from The Sugar Hill Gang) who

blew me away, I was so influenced by him and his William Burroughs cut

up ideas. He influenced me so much with all his sonic distortions, all

that funk stuff you know, mangled up, it just sounded like your radio

blowing up, or Jah Shaka's speaker system exploding! These were very

strange records I was making!"

In

Adrian Sherwood's words,"I was so inspired by the sheer amount

of innovative influences around me at that time. I was working with

Japanese musicians (Kishi, his wife who contributed eerie keyboards,

and classical far eastern instrumentation), then there were the African

musicians I met through Bonjo I (African Head Charge percussionist)

and it was then I met Mark Stewart, (ex Pop Group singer, and from Mark

Stewart and The Mafia, using the line up from The Sugar Hill Gang) who

blew me away, I was so influenced by him and his William Burroughs cut

up ideas. He influenced me so much with all his sonic distortions, all

that funk stuff you know, mangled up, it just sounded like your radio

blowing up, or Jah Shaka's speaker system exploding! These were very

strange records I was making!"

This was just as valid as the orthodox roots path from Jamaica, and indeed, took some of its inspiration from the same sources, but what ON U sound conspirators hurled at the listener was another kind of bizarre aural experience. The African Head Charge discs are still one of the eeriest listening experiences to be partaken of, animal cries, African chants, and industrial sounds from the streets of London, true environment sounds of the inner city urban jungle we inhabit, are mixed with crackling tapes of Einstein discussing the core of language acquisition and mental process, spliced up with pinging submarine tones, and brittle African percussion, Chinese harps, all underpinned by the primal throbbing bass of King Tubby and other Kingston dub innovators.

Besides the dub influence, there was another influence at work here: The avant garde free form jazz tradition of Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman and James Blood Ulmer, and this is especially apparent in the album 'My Life in A hole in The Ground'. Jamaica's renowned horns man Deadley Headley makes his mark here, (fresh from hard and crisp sessions with Jamaica's legendary mystic, Augustus Pablo and his Rockers label) playing eerie sax and other horn refrains, plaintive and harsh, invoking the spirit of ancient African memories, New Orleans melancholy shamanic jazz, and the avant garde euphoric attack of Pharaoh Sanders, Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry.

Duke Ellington referred to the creators of jazz sounds as "night creatures". When the listener hears 'My life In a Hole in the Ground', it is easy to see why such a description came his to mind. Stanley Crouch, African American social and political critic and novelist wrote of the musical tradition of Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and James Blood Ulmer in the following words, that their music was "held together by a sorrow that gradually rises to a sober joy ,giving the listener a feeling of being lifted up, which is the purpose of (all) music. Sounds that human beings make are as much for communication as for transformation, and to open oneself to such music was to become aware of music of perpetual transformation".

Such words are pertinent when listening to Adrian Sherwood's classic work with African Head Charge. With their first album, Adrian was clearly making a reference to another album he had loved, the equally ground breaking Brian Eno album, 'My Life in The Bush of Ghosts', which featured a cut up funk landscape, sampling Lebanese mountain shepherds, irate radio hosts and confessional priests. With African Head Charge, Adrian was answering back with a harshly avant garde, African dub reply. It was every bit as weird as Eno's offering, perhaps more so, going so far as to feature a track ('Far Away Chant') that just seemed to stop altogether at will, randomly, halfway through, the entire rhythm section disappearing only to come crashing in seconds later, pounding out a sticky and swirling rhythm, dark and threatening in equal measure.

His Dub Syndicate album of the same time was called 'Pounding Systems'. The title speaks volumes. This featured Jamaican legend Style Scott on drums, fresh from his works with Prince Far I, The Slits, and Kingston's cutting edge session band, The Roots Radics, who had made a name for themselves on the emerging dancehall scene. They were the Dons on the roots session recording scene at that time, recording surreal, echo drenched dub plates for King Tubby's, Prince Jammy and Scientist. Their sound was tight, dark and menacing. Deeply dread.

Just as great Jamaican innovators such as Keith Hudson had made radical leaps forward with albums like 'Flesh of my Skin', 'Blood of My Blood', (Of Keith Hudson and this work, Keith Levene stated that he, "loved that album and artist so much, I bought 'Flesh of my Skin' at least six times at different periods of my life.") African Head Charge and the other ONU dub releases were an urban answer, coming from the darkness of English winter. The sound emerged from the inner city wasteland and ghetto areas of London, but with a distinct African memory and with the serious dread of Rasta in exile in the cold, up against the wall in Babylon: African Head Charge. There had never been music quite like this before, and may never be in the future.

Adrian's

view of these African Head Charge releases is this, "You know,

all those records were a labour of love to me, and we didn't expect

too many financial rewards .When you listen to a record like 'Environmental

Studies' (African Head Charge's second release), it's clear that a sound

like that might be intimidating to some people. Woven in to the mix,

you can hear car crashes, water flowing, bottles breaking. We always

believed in those releases, and I felt they would have sounded incredible

as futuristic film soundtracks. It's true that some purists on the London

scene dissed me for those records I was producing at that time perhaps

it was the sheer unconventionality of the sound, the inability to be

able to categorise such a threatening sound. I didn't give a fuck about

the luddite purists with their little preserves. Really, they didn't

matter to me. I just went on to expand my experiments, putting out hard

dub records like 'Starship Africa'".

Adrian's

view of these African Head Charge releases is this, "You know,

all those records were a labour of love to me, and we didn't expect

too many financial rewards .When you listen to a record like 'Environmental

Studies' (African Head Charge's second release), it's clear that a sound

like that might be intimidating to some people. Woven in to the mix,

you can hear car crashes, water flowing, bottles breaking. We always

believed in those releases, and I felt they would have sounded incredible

as futuristic film soundtracks. It's true that some purists on the London

scene dissed me for those records I was producing at that time perhaps

it was the sheer unconventionality of the sound, the inability to be

able to categorise such a threatening sound. I didn't give a fuck about

the luddite purists with their little preserves. Really, they didn't

matter to me. I just went on to expand my experiments, putting out hard

dub records like 'Starship Africa'".

A heavy roots record by Creation Rebel featuring entire tracks made up of backward tape loops, industrial drills roaring, that style. ONU Sound releases always had a date on the back of the sleeve: Picking up an African Head Charge album from 1979, the date read 1989. A release from 1980 read 1990. 10 years in the future. And they were always ten years ahead of their time. At least ten years ahead of their time.

A later release 'Drastic Season' has already been plundered for ideas by current drum and bass and Junglist artists: check the track 'Depth Charge', with its slow burning syn drum intro, and distorted beats. It comes as no surprise to learn then, that current drum and bass artists such as Asian Dub Foundation have sought the services of Adrian Sherwood to engineer their new work, and even rock artists such as Primal Scream have made use of his engineering skills to deconstruct their rock sound into spatial dub dynamics. This is extreme noise distortion, played out in these eccentric sonic assaults, so strange that they caught the attention of film director David Lynch, who chose to include one of the African Head Charge tracks (a chant from the great Prince Far I with a voice so deep and dread intended to strike fear into the hearts of nuclear warmongers) in his award winning Cannes film festival movie 'Wild at Heart'.

David Lynch has always had an ear for heavy, dramatic soundscapes in his movies. In 'Lost Highway' Lynch had made use of the atmospheric bass menace of Barry Adamson's music, which lent itself perfectly to his melancholic and aggressively surreal film noir style, and Angelo Badalamenti's soundtrack contributions were both perversely sentimental and threatening at the same time. In 'Fire Walk With Me' Lynch and Badalamenti used veteran jazz bass players like Buster Williams and Ron Carter (who had both played with an overwhelming number of Jazz masters, from Miles Davis to Pharaoh Sanders) to great effect, bringing aspects of an inherent avant garde moody aggression existing in their sound, to the forefront. The resulting tracks featuring Buster Williams and Ron Carter were pieces that were heavy with atmosphere and foreboding, yet still retaining a deep, almost naïve and pure emotional quality. In 'Wild at Heart' Lynch used African Head Charge's sound to awesome effect, specifically in the unsettling scene in which Harry Dean Stanton meets his end in a ritual ceremony. Lynch took the original track, slowing it down, reducing it dramatically to a bass throb, a heartbeat pulse.

These 'made in London' ONU Sound records were undoubtedly genuine though, and not a self conscious attempt to imitate what had been going on in Jamaica these ONU sound records used the best of Jamaican talent and New York talent and fused it with an English off the wall sensibility, in part drawn from the extreme pool of experimentation that had emerged from punk in London at that time, and that includes a vast range of artists /avant garde luminaries, such as David Toop, Lol Coxhill and Steve Beresford, to the great bass and guitar creative duo from John Lydon's Public Image, Keith Levene and Jah Wobble.

By punk, what is meant is the original spirit of the music, a desire to seek the original, the challenging, the new, not a formulaic re hash of New York Dolls, MC5 or Stooges power chord attacks. The cream of London's punk inner circle had left behind those power chords back in 78 and 79. The tired and farcical Sex Pistols final performance at Winterland, San Fransisco, USA had witnessed the last limping ghost of that form of punk. Each member of the Sex Pistols had begun to hate and loathe one another, and that is so clearly apparent when watching film footage of that final pained concert. Each member of the band appear to be playing in bored and uninspired isolation, not even speaking to one another, or looking at each other, "This is no fun, why do I even bother?", " Ever get the feeling you've been cheated", were Johnny Rotten's final infamous words. Not long after, Sid Vicious, after indulging in months of self abuse and an ever increasing drug habit, was accused of the murder of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen. It wasn‚t long after that Vicious himself was dead.

Johnny

Rotten broke up the group and swore never to work with the Sex Pistols

again. Johnny Rotten reclaimed his real name of John Lydon, and launched

his awesome bass roar of Public Image. 'Metal Box' sounded off the Richter

scale in the weirdness stakes around '78, but to those who knew their

dub, it was clear where this disc was coming from: Dennis Morris noted

that he believed John Lydon had already absorbed the space and dynamics

of dub from his trip with Don Letts to Jamaica, and wanted to realise

its full possibilities on his return to the UK Whilst in Jamaica, Don

Letts and John Lydon had met all their „heroes on the roots and culture

scene at that time: Rebels, visionaries, chanters and mavericks, microphone

chanters like Prince Far I, Big Youth, and I Roy, and deeply spiritual

singers, The Congos, men who produced some of the greatest works of

that time.

Johnny

Rotten broke up the group and swore never to work with the Sex Pistols

again. Johnny Rotten reclaimed his real name of John Lydon, and launched

his awesome bass roar of Public Image. 'Metal Box' sounded off the Richter

scale in the weirdness stakes around '78, but to those who knew their

dub, it was clear where this disc was coming from: Dennis Morris noted

that he believed John Lydon had already absorbed the space and dynamics

of dub from his trip with Don Letts to Jamaica, and wanted to realise

its full possibilities on his return to the UK Whilst in Jamaica, Don

Letts and John Lydon had met all their „heroes on the roots and culture

scene at that time: Rebels, visionaries, chanters and mavericks, microphone

chanters like Prince Far I, Big Youth, and I Roy, and deeply spiritual

singers, The Congos, men who produced some of the greatest works of

that time.

Remembering that time, Don Letts says, "You know, sometimes me and John had to pinch ourselves to see we weren't dreaming! It was great for us to be meeting and working with these guys, guys whose music we really loved! As for the Rastas, they loved John! To them he was 'THE' Punk Don from London, you know, they were aware of all the trouble he'd stirred up in London, and yeah, they were into his stance and what he stood for. We smoked the chalice together with U Roy, and then went to one of URoy's sound system sessions, and let me tell you, it was LOUD. Both John and I, literally, passed out. I remember some guy shaking us awake, hours later. Wake up man, dance done! Yeah those days in Jamaica were wild times for me and John".

Dennis Morris also observed that even before the demise of The Sex Pistols, John Lydon was planning his next move with noted dub roots reggae fanatic Jah Wobble, one of the famed 'John's' gang made up of Sid (real name John Beverley), John Rotten, John Wardle (Jah Wobble), plus Lydon's friends John Gray and John Stevens (Rambo). They all came from North and East London, and went everywhere together, and were always to be seen hanging out down on the King‚s Road, either in Malcolm Mclaren's shop 'Sex' or at Don Letts 'Acme Attractions'. The rumour goes that whenever he was introduced to people, he would always retort with a drunken slur, "My name's John Wardle". No one could understand the slur, so he was christened Jah Wobble. This fitted perfectly since everyone knew he loved his dub roots reggae, as well as avant garde music such as Can and Eno.

Keith Levene had long been a big influence behind the scenes in the early days of the London punk inner circles. He had been one of the founder members of The Clash, taught The Slits how to play, and had played with Sid Vicious in the now legendary Flowers of Romance. Public Image/John Lydon, Keith Levene and Jah Wobble wanted to move away from the banal conservatism of rock to the space of dub dynamics. After all that was what had prompted Keith Levene to leave The Clash in the first place. In conversation with Jason Gross, Keith Levene recounts it this way, "I left the band cos I just got too depressed being in the band. They were embarrassing. They were just too lame for me. {the sound} just wasn't hard enough". Keith remembers how he met John Lydon, and that period of his life, "(in the late 70's) we all knew we were fucked. There were no jobs or, you could just go out there and be this straight stiff. When you're going to be in a band, you're either prepared to read music and be in an orchestra, or you're IN A BAND. Any band I was going to be in was going to be bad. We (The Clash) had already done gigs with the Pistols I remember John sitting miles away from the rest of the band members, looking miserable. There's me sitting in another corner, away from all my band members, looking miserable. So I went over to Lydon to talk to him we knew we were the best bands on the scene at that time. I said 'I'‚m out of here after this gig' and said to him, 'Do you wanna get a band together if the Pistols ever end'?

What resulted, what came to be when Lydon eventually did seek out the guitar skill and innovation of Keith Levene was the creation of a huge sound, unpredictable and uncontrived, relying on a seismic bass resonating under every tune, and with the melancholy guitar of Keith Levene skittering aggressively, but with an effortless groundbreaking innovative style, over the top. Again, as with dub music, this was by no means contrived, or music that made any concessions whatsoever to previously accepted musical conventions or form. Its main raison d'etre was originality in huge doses, echoing aspects of previous musical forms perhaps, but in no way imitating or copying anything that had gone before. Just listen to 'Metal Box's', 'Death Disco' (the lyrics were written to reconcile John Lydon to the passing of his mother from cancer), with Keith Levene evoking the tones of 'Swan Lake' on his guitar, riding high in the mix, sounding like an eerie drone, with Jah Wobble's threatening bass resonation's booming beneath the murky mix, and you know this is not quite like anything you have heard before.

But what the listener can't escape from when listening to 'Metal Box' is that sound, the eerie soundtrack like quality to it, the surreality of the space it creates in the listeners mind. It conjures up vivid, magical images a film director or novelist might take years to achieve. Firstly, there is the subterranean bass sound created. Keith Levene remarked, "For some engineers, all of this was very difficult. To get such a deep bass sound, it seemed to break every rule in the book. We had such a hard time with this, so when we had the mikes set up. I just told them to record everything. They didn't understand that though." Then there is the distinctive scything guitar sound. Commenting on that, Keith recounts, "I would play (a) chord and it would be like breaking glass in slow motion. My guitar was feeding back like mad. It seemed like it was just going on forever".

Some

guitar patterns he created, he described as the disintegration of playing

the guitar as a drone instrument John Lydon, Keith Levene and Jah Wobble,

although they had partially started the entire UK version of punk, and

contributed enormously to its musical force and momentum, had no wish

to continue with the by now conventional structures of so called 'punk'

music and a lot of their early concerts were just out of control, many

ending in riot (such as the infamous Ritz riot in America), or near

riot conditions. Keith Levene recounted a concert they played in Belgium,

soon after forming, which ended in Wobble and Levene threatening to

beat up bemused journalists backstage, and clashing with an audience

that just wasn't ready for them. The audience were punks, perhaps expecting

the Sex Pistols sound, and when they didn‚t get that, got restless,

"At one point, I just started burning their money, you know, I

just said, 'his is what I think of your fucking money!', and I started

burning their money in front of them on stage!"

Some

guitar patterns he created, he described as the disintegration of playing

the guitar as a drone instrument John Lydon, Keith Levene and Jah Wobble,

although they had partially started the entire UK version of punk, and

contributed enormously to its musical force and momentum, had no wish

to continue with the by now conventional structures of so called 'punk'

music and a lot of their early concerts were just out of control, many

ending in riot (such as the infamous Ritz riot in America), or near

riot conditions. Keith Levene recounted a concert they played in Belgium,

soon after forming, which ended in Wobble and Levene threatening to

beat up bemused journalists backstage, and clashing with an audience

that just wasn't ready for them. The audience were punks, perhaps expecting

the Sex Pistols sound, and when they didn‚t get that, got restless,

"At one point, I just started burning their money, you know, I

just said, 'his is what I think of your fucking money!', and I started

burning their money in front of them on stage!"

James Blood Ulmer referred to Public Image as one of the few bands who went 'beyond music'. That much is clear. Keith Levene expresses it this way, "What was important was putting across a message: Getting the band off the stage and the audience on the stage, getting out there and being an anti-star, going out there and saying, 'you can do what the fuck you want!' So therefore, its no holds barred. What's constricting you these are things like tornadoes, things just end up a certain way."

Never happy to imitate, they had made this project unique, and by the time 'Flowers of Romance' emerged, their barriers had been pushed back even further, offering up a record that deliberately further ignored any of the conventions of rock's ordinary patterns and stances. The listener hears a record featuring massively amplified drums, fire extinguishers exploding, a bass is played with a violin bow to produce a hypnotic, droning quality, what sounds almost like medieval folk melody patterns mix with echoes of Jamaican dub techniques with Keith Levene even miking up a television on one particular track to produce a thoroughly disconcerting sound. On another track, Keith Levene went as far as picking up some discarded tape off the studio floor, looping it, and producing a backing track from it. Easy, comfortable listening this is not, but it is in places, undoubtedly a powerful and strangely compelling listening experience.

In many people's eyes, this was to be the end of the high point of John Lydon's self expression, and not long later we see members of his band leaving to work with Adrian Sherwood from the London based ON U sound. Some consider that Lydon really needed the creative axis of Levene and Jah Wobble to realise his inner visions, to give form to his imagination. It has been said that before Public Image, audiences never bothered to listen for the bass rhythms in rock music, but Lydon, Levene and Wobble had introduced a dub sensibility into rock, with its emphasis on space, echo, texture and a deep, all consuming bass.

By this time, Adrian Sherwood of ONU sound was working with the best of European dub roots talent, as well as Jamaica's heroes, and it would only be a matter of time before he crossed paths with Lee Scratch Perry .The extraordinary man Lee Perry was known for his bizarre eccentricity, the peak of which saw him burn down his own legendary Black Ark studio, then seen walking backward and striking the earth with a hammer! The reason for his sudden breakdown and destruction of his own magical Black Ark studio are as yet unknown, or best known to the genius madman himself. Still, eccentricity aside, Lee Perry has produced some of the most powerful works of genius to come out of Jamaica, a genius much respected by many artists even outside the reggae fold such as Paul McCartney and The Clash who queued outside his infamous Black Ark studios to receive his transmission of wisdom, and for him to give their records his extraordinarily rich, deep and textured treatment. It was said that Lee Perry was a kind of voodoo magician, an artist of the greatness of Salvador Dali, and the bizarre decorations (children's toys, pages ripped from medical text books, Gnostic signs and symbols, superman paintings, hand and foot prints all the way up the wall to the roof, Kabbalistic number codes and scrawled hand writing covering nearly every inch of the walls) adorning his studio went some way to supporting such a theory. Some said he was a Jamaican Phil Spector, or Brian Eno.

Adrian Sherwood had come up from the classic rebel roots pedigree, living in a squat with punk dub innovators, The Slits, and later, after the death of Sid Vicious, linking up with John Lydon and his band of determined explorers, Keith Levene and Jah Wobble. Adrian's insistence on a completely original, sometimes otherworldly sound made him a perfect foil, partner and sound collaborator for Lee Perry. Together they produced music of an ethereal energy and poly-rhythmic force. The Jamaican legend had joined forces with a contemporary UK sound rebel, and the results were awesome.

Speaking of this whole period of experimentation and innovation, and meeting up with John Lydon and members of Public Image, Sherwood Adrian expresses his memories this way, "Going back to the influence of punk days now, yeah, I knew John Lydon well, and it was through John Lydon that I got to know Keith Levene and Jah Wobble. Ari Upp, (singer from The Slits) Neneh Cherry (daughter of Don Cherry), Junior and I, we all lived together in a squat down Battersea way, and John Lydon was living with Nora (his future wife and mother of Ari Upp) round the corner. John Lydon used to visit us, and we all hung out together. John was just so hip you know, a lot of people really looked up to him at that time. John really knew his reggae, he loved his reggae. I can tell you that John Lydon really helped the progress of reggae and roots and culture in Britain at that time. It was around that time, not long after he'd been badly beaten up here in London, that he went onto the radio and played Dr Alimantado's 'Born for a Purpose'. Alimantado was immediately shot to cult status as a result! The lyric of that tune was relevant you know? 'If you feel like you have no reason for living, don't determine my life!' That was John's reply to the idiots who had beaten him up. You should realise that it was John Lydon who suggested that I work with Keith Levene who I was really impressed by, and then through him I linked up with Jah Wobble (both from Public Image) , which was great for me at the time. I was so happy to work with Keith, because Keith just had such an original sound, and I knew I could translate that originality he had in to a dub context, and it worked totally if you listen to those Creation Rebel records. He also played on those New Age Steppers sessions, and laid down some bass as well on some tracks, which I don't think he was ever credited for. Keith was always so into the Beatles, that was Keith's thing .So it was John Lydon who had the idea for me to work with his band, and I loved their sound and what they were doing. As for Jah Wobble, I love him, and I respect what he has become as a person and a musician. Jah Wobble really understands his instrument; he is the Original Mr FAT BASS SOUND. That is Wobble for you. He has left behind his difficulties with alcohol, and really progressed. The last time I saw him was at his wedding and he looked so happy. I'm proud of the stuff Wobble has done with me on those Dub Syndicate and African Head Charge records."

Levene remembers the sessions with Dub Syndicate and Singers and Players/Creation Rebel this way, "Look man, my intention, my playing on some of those tracks was pretty sparse, (check 'Sit and Wonder' with Bim Sherman or 'Quante Jubilawith' Prince Far I), because you know, guitar playing is like speech, if you don't have anything to say, don't fucking say it, so that was my intention with those tracks. Creation Rebel and African Head Charge understood totally where I was coming from and yeah, they were into it. They used to call me 'The Professor', so it was like, Bonjo I and Crucial Tony would say, 'oh, here comes Keith the Professor to lay down his thing.' We understood each other. And Bim Sherman sang beautifully, like Gregory Isaacs. I did the tracks and Adrian did what he does best, just took them apart, deconstructed them".

The sound system heritage has been continued in London by bands like Disciples, and Jah Warrior, who have continued making orthodox roots spiritual music, stepping out of Babylon with a positive message. The Disciples sound is innovative, playing sinewy and funky bass rhythms, poly textured percussive breaks and including what some listeners would consider a harsh, austere industrial edge to the traditional roots sound, leading the roots and culture audience to a progression forward into the year 2002. Disciples have come out of the extreme Jah Shaka sound system culture, starting out by contributing some hard dub plates for Jah Shaka's sound system. The Disciples very quickly made a name for themselves from these dub plates, featuring towering and inspired bass lines, replete with shattering reverb and echo. These are harsh, disciplined sounds, roots and culture music, but in no way clichéd or following strictly defined conventions. The sounds are clearly drawn from a deep Jamaican musical source, but it is apparent that Disciples have other roots, and echoes of thundering bass lines from Pharaoh Sanders and Alice Coltrane records are audible in these tunes. In the loops and harsh repetitive drum patterns, there is also an industrial aggression and precision, though none of this is contrived or self consciously done. In the final analysis, Disciples music is spiritual reggae music, and good enough to stand up there with the best of current Jamaican studio offerings, such as the sounds currently emerging from Kingston's Xterminator label.

This

is no mean feat, and Disciples deserve the accolades they receive. Jah

Shaka saw the awesome and original vibes that Disciples had, and drew

them into his fold, releasing their music on his own Jah Shaka King

of the Zulu Tribe record label, an honour to anyone who knows, who deeply

understands the power of bass culture, and the place Shaka has within

that gnostic world. Russ Disciples (also part of Boomshakalaka sound

system) puts it this way, "Now let me tell you about our initiation

into sound system, and our initiation into that world, which came through

Jah Shaka. You check out a sound system like that, and the only word

to be used is intense, with a bass vibration thrashing around. Now,

once you hear that well, we decided we wanted that serious intensity

too, for sure. I'm looking for that depth in my sound".

This

is no mean feat, and Disciples deserve the accolades they receive. Jah

Shaka saw the awesome and original vibes that Disciples had, and drew

them into his fold, releasing their music on his own Jah Shaka King

of the Zulu Tribe record label, an honour to anyone who knows, who deeply

understands the power of bass culture, and the place Shaka has within

that gnostic world. Russ Disciples (also part of Boomshakalaka sound

system) puts it this way, "Now let me tell you about our initiation

into sound system, and our initiation into that world, which came through

Jah Shaka. You check out a sound system like that, and the only word

to be used is intense, with a bass vibration thrashing around. Now,

once you hear that well, we decided we wanted that serious intensity

too, for sure. I'm looking for that depth in my sound".

Listening to 'Resonations' and 'For those who Understand', the listener hears sounds of inspiration, a spiritual, focussed sound of awesome force: Harsh drums patterns twinned with disciplined, funky keyboard patterns, and weaving, liquid bass rhythms. Played over a sound system, these are tunes that can crush the air from your chest, the bass and shattering echo moving, literally, like a natural force, a wind force. You feel sound system, rather than solely hearing it: Disciples tunes exemplify this: Physical power, but with the inspirational role of the griot very much present. "When I play sound system, I play music with a message, and that is very deep with me, I hope people pick up on this, you know, because that is very important to me. That is just what I feel you know, I feel it's my duty to do that, without any suggestion of preaching, I must emphasise that, but reggae music is music of the heart, so the music has to get into your heart. You have to ask yourself, why are you checking out reggae? It's heart music, message music. Energy music. I feel this music that I play". How does the music he plays, roots music, differ from the lighter, dancehall/bashment music? "Well, that music, the dancehall vibe doesn't ask any questions of the listener, doesn't demand anything from the listener. Roots music is compelling. Mentally, there is a focus and certain seriousness, a depth present".

Some facts are becoming increasingly obvious: Both in UK and abroad, there appears to be a longing for this kind of music, wherever it is played, music with deep spiritual undertones, a serious intent, and not pandering to the shallowness of commercial culture and musical forms. Another thread is that taken up by Junglists, Congo Natty, and Smith and Mighty/AKA More Rockers, who have carried on with the subsonic bass resonation's of dub roots and culture, but within a Junglist format. Early Junglist styles had progressed from orthodox roots and culture and ragga dancehall, using the same seismic, consciousness shifting bass lines, but adding their own innovative severely splintered drumming patterns, which proved that innovation and creativity were still moving forward in UK.

This was a strictly UK creation, which the rest of the world have not been able to catch up with. The drumming patterns especially, were completely original, an unheard phenomenon prior to their English incarnation. The track would begin with some conventional strings perhaps, or a Rastafari chant to the creator, only to break down utterly in to drum rhythms and patterns which sounded wrong somehow, out of time, out of rhythm, too fast, discordant, and it was only when the seismic dub bass dropped in to the mix with awesome force, paired with a righteous reggae lyric, that the whole piece seemed to come together into any recognisable whole, suddenly it made sense, as the bass moved your soul and your feet. But still, it was drawing its inspiration from that original, earlier spiritual and cultural well spring of bass culture. In UK, this scene is refreshingly integrated and colour blind, as the soft spoken and thoughtful Rob Smith of More Rockers and Smith and Mighty explains, "Music forms a secret language which transcends colour and the restraints of a restrictive mind". Speaking with the other central figure on the Junglist scene in London, Congo Natty, it is clear that spiritual commitment is the driving motivation behind his deep bass grooves. He means it, and his muse is, as it was in Shaka's roots and culture sound, the biblical spiritual giant, King David and King David‚s meditative music, and the results are still, deeply, deeply dread.

What

stands out about all these artists is an urge and inclination to produce

sound and noise which isn't easily categorised and tainted by cynical

corporate design and pre packaging. It seems obvious that dance culture

is partially in the grips of a conservative, un adventurous mindset,

in which people are only willing to accept a music form once it has

been labelled, packaged and presented in a named, easily categorisable,

digestible form. DJ's and music magazines fall over each other in their

rush to think up new categories, and it isn't long before a new music

magazine is on the racks, with added free CD, featuring hard step jungle,

old skool jungle, ragga revive Jungle, 2 step garage, ragga garage,

hardcore jungle, intelligent drum and bass .There seems to be a deep

need to categorise, which in effect, institutionalises a form, turns

it into just another saleable commodity, a convention. Every month the

clubs and dance music press seem to invent a new category, which in

truth, isn't radically different from the previous months. Do you remember

the story of the emperor's new clothes?

What

stands out about all these artists is an urge and inclination to produce

sound and noise which isn't easily categorised and tainted by cynical

corporate design and pre packaging. It seems obvious that dance culture

is partially in the grips of a conservative, un adventurous mindset,

in which people are only willing to accept a music form once it has

been labelled, packaged and presented in a named, easily categorisable,

digestible form. DJ's and music magazines fall over each other in their

rush to think up new categories, and it isn't long before a new music

magazine is on the racks, with added free CD, featuring hard step jungle,

old skool jungle, ragga revive Jungle, 2 step garage, ragga garage,

hardcore jungle, intelligent drum and bass .There seems to be a deep

need to categorise, which in effect, institutionalises a form, turns

it into just another saleable commodity, a convention. Every month the

clubs and dance music press seem to invent a new category, which in

truth, isn't radically different from the previous months. Do you remember

the story of the emperor's new clothes?

When This Heat put out '24 track Tape Loop', or 23 Skidoo produced the innovative rush of energy (on the 'Seven Songs' album produced by Psychic T.V's Genesis. P. Orridge), Kundalini, being part of a category or meeting a convention was the last thing on their minds, and as a result, even 25 years or so later, these tracks still sound fresh and original. (Check the Soul Jazz compilation,'In the Beginning there was Rhythm' for proof. The track by This Heat, '24 Track Tape Loop' predates jungle rhythms by about twenty years, and Skidoo's 'Coup' was unashamedly stolen almost in its entirety by Chemical Bros in 'Block Rockin Beats': The difference being that 23 Skidoo had created the hypnotic , mantra like rhythm some 20 years before, in an atmosphere of striving to produce something of originality.

Adrian Sherwood, remembering the germination of ideas in the late 70's, when all these musical forms were creating environments and ideas eventually to go on and bear full fruit in the 90's and the 21st century, expresses it this way, "When I hear Jungle and drum and bass artists saying that ONU sound influenced them, well I feel that is very kind, because you know as Rasta philosophy tells it, 'each one teach one', you know, and I was influenced by so many people too, so I'm glad that this vibe is continuing. Back in the late 70's we used to play heavy gigs with Creation Rebel, and everyone used to come and check us out, you know? The Clash would be there, The Slits, people from Public Image, John Lydon's entourage, and that time, it was so great when I reflect because we were all into the same heavy groundbreaking tunes, heavy roots music of all varieties, and it was shaping so many of the things that happened then, later, and now! You know so many things which just seemed bizarre at the time when we were experimenting have since happened in music, for example hip hop beats fused with harsh and heavy guitar chords, or totally bass centred music which has now become such a part of the mainstream."

Copyright/legally

protected by publication law:

October 2002

First

Published 3am Magazine, October 2002

© 2002 Greg Whitfield

This expanded version republished Fodderstompf, October 2002

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Greg Whitfield has spent most of the last twelve years living in London and the Far East, specifically Korea, where his wife is a Korean classical musician. He is currently engaged in researching and writing a book on the avant garde/sound system and bass culture, which has been emerging out of London over the last twenty-five years up until the present time. He loves Dadaism, conscious music and literature, and, of course, very loud bass.

![]()

Jamaican Sound System © unknown

John Lydon in Jamaica, February 1978 © Dennis Morris

The Steel Leg EP, 1978 © unknown

Ade Sherwood in the studio © unknown

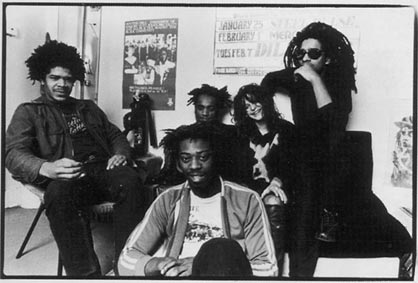

Creation Rebel New Age Steppers: Threat to Creation, 1982 © unknown

John Lydon in Jamaica, February 1978 © Dennis Morris

Keith Levene & John Lydon; circa 1979/80 © unknown

PiL; circa 1981, Jeanette Lee, John Lydon, Keith Levene © unknown

Don Letts Dub Cartell © unknown

Greg Whitfield 2002 © Greg Whitfield